AbstractPURPOSEAn increase in bone mineral density during adolescence increases resistance to fractures in older age. The Korean Society for Bone and Mineral Research and the Korean Society of Exercise Physiology developed exercise guidelines to increase the peak bone mass (PBM) in adolescents based on evidence through a systematic review of previous research.

METHODSArticles were selected using the systematic method, and the exercise guidelines were established by selecting key questions (KQs) and defining the effects of exercises based on evidence through a literature review for selecting the final exercise method. There were 9 KQs. An online search was conducted on articles published since 2000, and 93 articles were identified.

RESULTSAn increase in PBM in adolescence was effective for preventing osteoporosis and fractures in older age. Exercise programs as part of vigorous physical activity (VPA) including resistance and impact exercise at least 5 to 6 months were effective for improving PBM in adolescents. It is recommended that resistance exercise is performed 10 to 12 rep·set-1 1-2 set·region-1 and 3 days·week-1 using the large muscles. For impact exercises such as jumping, it is recommended that the exercise is performed at least 50 jumps·min-1, 10 min·day-1, and 2 days·week-1.

CONCLUSIONSExercise guidelines were successfully developed, and they recommend at least 5 to 6 months of VPA, which includes both resistance and impact exercises. With the development of exercise guidelines, the incidence of osteoporosis and fractures in the aging society can be reduced in the future, thus contributing to improved public health.

INTRODUCTION뼈는 살아있는 구조물로 기계적인 스트레스에 반응하여 환경적 요구에 적응한다. 기계적 강도에는 역치(Minimum effective strain, MES)가 존재하여 강도가 낮으면 골 흡수가 일어나고 일정 강도 이상일 때는 골 형성이 일어나 골밀도(Bone mineral density, BMD)가 증가한다[1]. 기계적 부하가 제한되는 우주비행과 침상 휴식(Bed rests) 등은 골밀도를 감소시키지만[2], 지속적인 기계적 부하는 골밀도를 증가시키며[3], 이는 정기적인 적절한 운동이 골밀도를 증가시키는 것에 잘 나타난다. 테니스 선수의 경우 주로 사용하는 팔의 골밀도가 반대 팔과 비교하여 유의하게 골밀도가 높은 것이 보고되는 것처럼, 기계적 강도에 대한 뼈의 반응은 국소적으로 일어난다[4].

한편, 나이가 들어가면서 골밀도는 감소하고 이것은 골절을 증가시킨다. 미국보건복지부(U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, USDHHS)는 50세의 여성의 약 30-50%와 남성의 약 15-20%는 남은 생애 동안 골다공증성 골절을 겪을 것으로 보고하고 있다[5]. 따라서 골절을 예방하기 위해서 골밀도를 높게 유지하는 것이 중요하다. 미국스포츠의학회(American college of sport medicine, ACSM)은 골절 저항력을 높이기 위한 일반적인 두 가지 전략을 제시했다[6]. 하나는 초기 30년 동안 골밀도의 증가를 극대화시키고, 다른 하나는 내분비 변화, 노화, 신체활동 감소 등으로 인한 40세 이후 골밀도의 감소를 최소화하는 것이다. 특히 청소년 시절의 골밀도의 증가는 노인이 되었을 때의 골절 저항력을 높일 것이다[6]. 대부분의 역학 연구에서도 유년기 동안의 골밀도 증가는 노년기의 골감소에 의한 골절 위험을 감소시키는 것으로 보고되고 있다[7]. 통계적인 예측에서도 사춘기와 이른 성인기에 성취한 최대골량(Peak bone mass, PBM)은 노년기의 골다공증 위험의 강력한 예측 변수라는 것을 보여준다[8]. Clark 등[9]은 유년기 동안 골량(Bone mass)의 1표준 편차(SD) 감소는 성인기의 골절 위험을 89% 증가시킨다고 주장하고 있다. 늦은 성인기의 뼈 손실 예방만큼이나 청소년기의 골량 증가는 골절 예방에 중요하다[10]. 골다공증과 골절 예방을 위하여 일생 동안 뼈 건강 전략을 세워야 하며, 특히 조기에 시작할수록 이점이 많다.

성장기에 골밀도를 높이기 위한 전략 중에서 가장 효과적인 것이 운동을 포함한 활발한 신체 활동이다[11]. 활동적인 신체 활동이 골밀도와 골강도 증가와 함께 뼈의 구조적 개선을 가장 효과적으로 가져오는 것이 알려져 있다[12]. 그러나 미국의 12-19세 청소년 중 90% 이상이 신체 활동이 불충분하다고 보고되고 있으며[12], 불행하게도 우리나라의 청소년들 역시 하루에 한 시간 정도 운동을 하는 비율은 4.8%에 불과하다 할 정도로 신체활동이 불충분한 실정이다[13]. 또한 우리나라 청소년의 권장 운동량을 주150분 이상, 주 3회 이상의 격렬한 운동으로 정하여 평가할 때, 운동 실천율은 초등학생 52.0%, 중학생 31.4%, 고등학생 22.0%으로 고학년이 될수록 낮아진다[14]. 특히, 청소년기의 골밀도 변화는 신체활동에 민감하게 반응하기 때문에[10], 청소년기에 신체활동 수준의 급격한 감소는 최대골량의 수준을 저하시킬 위험이 있으며, 청소년기의 최대골량 수준의 감소는 노년기의 골다공증과 골절 발생률을 높일 가능성이 있다고 판단된다. 따라서 향후 고령사회의 골다공증 및 골절 발생률을 낮추기 위해서도 운동을 통한 신체 활동을 증가시켜 청소년들의 최대골량을 증가시키는 노력이 필요하다. 선행연구들이 청소년들의 골밀도를 높이는 다양한 운동방법을 제시하고 있으나, 운동 효과나 구체적인 운동 방법이 정리되어 있지 않아서 실제현장 적용이 어려운 상황이다. 이러한 이유로 대한골대사학회(The Korean Society for Bone and Mineral Research, KSBMR)과 한국운동생리학회(Korean Society of Exercise Physiology, KSEP)에서는 선행연구의 체계적인 문헌 검토를 통하여 근거에 기반한 청소년들의 최대골량을 높이기 위한 운동 가이드라인을 개발하게 되었다. 이 가이드라인을 활용하여 사회 저변의 스포츠 현장은 물론 중 고교 등의 학교 체육 현장에서 청소년들의 최대골량을 증가시키기 위한 운동법으로 활용되기를 기대한다.

METHODS이 가이드라인은 우리나라 청소년들의 최대골량을 증진시킬 수 있는 집약적인 운동방법을 제시하기 위하여 개발되었다. 대한골대사학회과 한국운동생리학회에서는 청소년 최대골량 증진을 위한 운동 가이드라인을 개발하기 위해 개발위원회(운동위원회)를 구성하였다. 이 위원회는 다분야 및 복수 기관으로 구성되었으며, 운동의학자, 운동현장전문인, 정형외과 의사를 포함하였다. 다음과 같이 체계적인 방법에 의하여 문헌을 선정하고, 핵심질문을 선택하고, 문헌 검토를 통하여 근거에 기반한 운동 효과를 규정하고, 최종 운동방법을 선정하여 운동 가이드라인을 채택하였다(Table 1).

1. 가이드라인 개발 프레임워크본 지침서를 개발하는 과정은 계획 및 개발, 마무리로 크게 3단계로 구성하였다[15]. 각 단계는 총 12개의 단계로 나누었다. 1단계는 계획 단계로 주제 선정하였으며(1st step), 개발 위원회 구성(2nd step), 이전에 발표된 지침 검토(3rd step), 개발 계획 수립(4th step), 핵심 질문(Key questions, KQ) 선택(5th step)으로 진행하였다. 2단계 개발 단계는 증거 검색, 평가 및 합성(6-8th step), 권고사항 작성 및 권고 등급 결정(9th step) 및 합의 구축(10th step)으로 구성하였다. 3단계 마무리 단계는 외부 검토와 출판물로 구성하였다(11-12th step).

2. 핵심 질문의 선정운동 가이드라인 결정을 위하여 검토할 핵심 질문을 선택하기 위해, 총 6명으로 구성된 운동위원회가 미국[6], 캐나다[16], 호주[17]에서 개발된 POSITION STATEMENT을 검토하였고, 미국체육학회(SHAPE America)가 발표한 아동 및 청소년의 신체활동과 뼈 건강에 관한 리뷰 논문을 검토하였다[24]. 또한, 미국 질병통제예방센터(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC)에서 발표한 미국인을 위한 신체활동 지침(제2판)을 참고 하였다[18]. 그 후 운동위원회는 국내 상황과 임상적 중요성을 고려하여 가장 관련성이 높은 12개의 핵심 질문을 선정하고, 최종적으로 9개의 최종 목록을 선택하였다(Table 1). 핵심 질문의 운동 방법으로는 빈도(F), 강도(I), 형태(T), 시간(T) 등이 포함되었다.

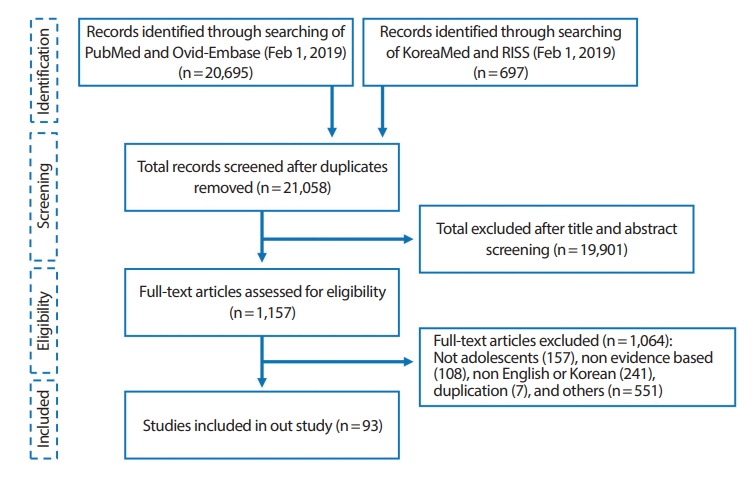

3. 문헌 검색운동위원회는 미국국립의학도서관(The United States National Library of Medicine, NLM)의 Public domain information on NLM(PubMed), 엘스비어사(Elsevier)의 Excerpta Medica dataBASE (EMBASE), 대한의학학술지편집인협의회(Korean Association of Medical Journal Editors, KAMJE)의 KoreaMed, 한국교육학술정보원(The Korea Education and Research Information Service, KERIS)의 Research Information Sharing Service (RISS) 등의 데이터베이스를 활용하여 체계적인 문헌 검색을 수행하였다. 문헌 검색을 위한 관련 키워드는 [aerobic OR endurance OR resistance OR power OR plyometric OR exercises OR “physical activities”] and [Bone OR BMD OR “bone metabolism”] and adolescents로 하였다. 논문 검토 단계에서는 systematic review을 위한 문헌의 범위를 결정하기 위해 PICOTS(대상자, 중재 방법, 비교 집단, 결과 변인, 결과 측정 시기, 연구 설계 디자인) 프레임을 사용하였다[20]. 온라인 검색은 2000년 이후로 발행된 논문을 대상으로 하고, 중복 연구는 EndNote 프로그램(Thomson Reuters Co.)을 사용하여 제거하였으며, 중복물을 제외한 21,058편의 관련 논문을 확인하였다. 그 결과 가장 관련성이 높은 1,157편 논문으로 좁히고, not adolescents (157편), non evidence based (108편), non English or Korean (241편), duplication(7편), and others (n=551편)를 제외하여 최종적으로 93편의 논문을 선정하였다(Fig. 1). 최종 선정된 논문은 systematic review을 포함하여 PICOTS가 명확한 실험적 논문들로, 운동위원회가 선정한 핵심 질문에 대한 근거 기반의 결론을 제공하는 논문들이었다.

4. 가이드라인의 최종 선정 및 작성 절차운동위원회는 최종 선정된 논문의 문헌 연구를 통하여 각 핵심 질문에 해당하는 근거를 검토한 후, 핵심 질문에 대한 답변으로써 주요 연구 내용을 요약하였다. 각 핵심 질문에 대한 답변으로 그 근거가 부족하거나 임상적 해석이 필요한 경우, 운동 위원회 위원들 사이에 합의를 진행하여 결정하였다. 근거의 강도는 5단계로 나누었다(Table 2). 그 후 모든 위원회 위원들의 의견을 수렴한 후 최종 권고안을 완성하였다. 이 과정에서 최종 가이드라인 권고안의 수용가능성과 적용가능성을 평가하였으며, 근거 및 운동 효과의 수준, 대상자의 만족도 등을 고려하여 권장 정도를 제시하였다. 권고 등급은 운동위원회의 동의와 함께 80% 이상의 합의 원칙에 따라 정하였다(Table 3).

RESULTS1. 핵심 질문1: 청소년기의 최대골량 증가는 노인기의 골다공증 및 골절 예방에 효과적인가?골염량(bone mineral contents, BMC)은 아동기에 걸쳐 상대적으로 천천히 축적되지만, 사춘기가 시작되고 신장이 급격하게 증가하여 최대 신장을 달성한 직후 골의 미네랄 축적은 급속히 최대치에 도달한다. 유럽 청소년의 경우, 최대 골밀도 축적률은 여아 12.5±0.90 세, 소년 14.1± 0.95 세에서 나타난다[21]. 골의 축적이 최대에 이르는 4년 동안(여아 8.5세, 남아 10.1세), 전체 신체 뼈 미네랄의 39%가 획득되고, 정점에 이르고 나서 4년 후(여아 16.5세, 남아 18.1세), 성인 골 질량의 95%가 달성된다[22]. 따라서 급속한 축적이 이루어지는 이 기간에 최대 골 염량을 최적화하는 것이 노인기의 골다공증 및 골절 예방에 효과적일 수 있다. 하지만 이러한 결론을 얻기 위해서는 젊은 성인기에 최대골량이 달성된 후 같은 기간 동안 같은 비율로 골량이 손실된다는 가정이 성립되어야 할 것이다. 다행히도 젊은 성인기에 달성된 최대골량이 높을수록 최대골량이 낮은 사람에 비교할 때 골염량 손실 기간이 더 길 수 있으며, 노년기의 골절 발생시기를 늦을 수 있다는 것이 널리 받아들여지고 있다. 또한 여성의 최대 골량이 부위마다 차이가 있으나(요추 골밀도: 33-40세, 고관절 골밀도: 16-19세)[23], 청소년 초기에는 신체 활동에 대한 뼈의 반응이 가장 활발한 시기로 알려져 있으며[24], 이 시기의 최대골량의 증가는 노인기의 골다공증 및 골절 예방에 효과적일 수 있다. 과거 청소년기에 엘리트 축구선수 출신인 평균연령 69세(53-93세)의 남성을 특별한 운동 경험이 없는 대조 집단(70세, n=1,368)과 비교한 연구에서, 위팔뼈 근위부(Proximal humerus), 노뼈 원위부(Distal radius), 척추뼈(Vertebra), 골반(Pelvis), 엉덩관절(Hip joint), 종아리뼈 관절구(Tibial condyle) 등의 취약 골절(Fragility fracture)의 발생률이 과거 축구선수 출신이 더 낮은 것으로 밝혀졌다[25]. Berger [23]의 연구에서도 8-15세 때의 신체 활동이 활발했던 어린이와 청소년이 그렇지 않은 사람들에 비해 젊은 성인 시기일 때(23-30세)의 엉덩이 골염량이 8%-10% 더 높다고 보고되고 있다. 이 연구들은 청소년기의 신체 활동이 성인 또는 노인기의 골절에 대해서 장기적이면서도 지속적인 이점을 제공하고 있을 가능성을 제시하는 것이라 생각된다. 또한 다른 대다수의 연구들에서도 높은 수준의 신체 활동에 참여하는 것이 활동적이지 못한 집단에 비교하여 더 큰 골량증가와 관련된다는 것을 설득력 있게 보여준다[26]. 따라서 청소년기의 최대골량 증가는 노인기의 골다공증 및 골절 예방에 효과적이라고 할 수 있다.

2. 핵심 질문2: 신체활동은 청소년기의 골밀도 향상에 효과적인가?청소년시기에서 신체활동(Physical activity, PA) 중의 하나인 스포츠의 실행은 성별, 연령 및 체지방과 상관없이 골밀도 값과 높은 상관 관계가 있다[26]. 사춘기 성장에 걸쳐 뼈의 강도를 결정하는 요인에 신체활동이 중요하며 골밀도는 물론 골미세구조에도 좋은 영향을 미친다[27]. 또한 청소년 시기의 신체활동은 젊은 성인기의 근위부 대퇴골에서 입체적인 뼈 구조의 강도를 더 높여준다. 사춘기에서의 신체 활동 수준이 크게 감소하였더라도 높은 수준의 신체 활동을 청소년기에 수행한다면, 뼈의 강도를 낮추지 않을 뿐만 아니라 뼈의 건강에 지속적으로 영향을 미칠 가능성이 있다[28]. 따라서 평생 동안의 골격 건강을 유지하고 골절 위험을 줄이기 위한 방법으로 청소년기의 신체활동이 좋은 전략이 될 것이다[29-31].

3. 핵심 질문3: 청소년기의 최대골량을 높이기 위해서는 어떻게 신체활동을 하면 효과적인가?격렬한 신체 활동(Vigorous physical activity, VPA)은 청소년의 골 형성을 촉진시키는 것으로 알려져있다. 하루 15분 이상의 격렬한 신체활동은 청소년의 대퇴경부(Femoral neck, FN)의 골밀도를 개선시키는 것으로 알려져 있으며[32], 유전적으로 청소년기의 요추 골밀도의 감소뿐만 아니라 성인기의 골밀도 감소를 일으키는 어린이들에게도 지속적으로 고강도 신체활동을 부하하면 엉덩 관절과 요추의 골밀도를 높인다고 보고되고 있다[26]. 특히, 점프를 포함하여 체중의 무게가 부하되는 하중은 뼈를 자극하는데 필수적인 것으로 여겨진다[33]. 활발한 신체 활동은 다리와 전신의 골밀도를 향상시킨다는 보고[34]는 이를 뒷받침하며, 따라서, 점프와 같이 격렬하고 고강도의 하중을 견디는 신체활동은 청소년기의 최대골량을 향상시키는 데 효과적이라고 생각된다(Table 4).

4. 핵심 질문4: 유산소 운동은 청소년기의 골밀도 향상에 효과적인가?유산소 운동은 낮은 강도로 장시간 지속하는 운동방식으로 체내의 지질이 주 연료로 사용되어 체지방감소를 통한 체중관리를 주목적으로 활용되는 경우가 많다. 유산소 운동의 대표적인 종류는 달리기, 걷기, 수영, 자전거 등이며, 이는 청소년기 골밀도 향상에는 긍정적인 측면과 동시에 부정적인 측면도 보고되고 있다. Eliakim 등[35]의 연구에 의하면 38명의 남자청소년을 대상으로 러닝, 에어로빅 댄스, 농구 등 유산소 운동 트레이닝을 하루 2시간, 주 5일, 5주간 실시한 결과, 골형성 지표인 Osteocalcin (OC), Bone Specific Alkaline Phosphatase(BSAP), procollagen-I C terminal propeptide (PICP)는 증가하였으며 골흡수 지표인 urinary cross-linked N-telopeptide of type I collagen (NTX)는 감소하는 것으로 나타났다. 또한, Im 등[36]의 여자 청소년을 대상으로 육상 운동 프로그램을 12주간 실시한 연구에 의하면 요부 및 대퇴부 골밀도가 향상되는 것으로 확인되었다. 더욱이, 여러 가지 형태의 청소년 운동선수 (달리기, 걷기, 사이클, 트라이애슬론, 축구)들을 대상으로 골밀도를 비교한 연구에서도 달리기[1], 소프트볼[37], 축구[38] 선수들에서 통계적으로 유의하게 높은 수치를 보였다. 이처럼 유산소 운동 중에서도 달리기처럼 체중의 하중을 받는 운동(Weight bearing exercise)프로그램 수행은 청소년기의 최대골량 향상에 효과적일 것이라고 생각된다.

하지만, 18-44세의 지구성달리기 선수들을 대상으로 달리는 거리와 요추 골밀도의 상관관계를 분석한 결과 유의한 부적 상관이 있는 것으로 나타났는데[39], 이러한 결과는 연령에 상관없이 일주일에 10 km 이상 달리 경우 골절(골밀도 악화)의 위험성을 제기하면서 달리는 거리를 조절해야 한다고 주장한 연구의 결과를 뒷받침한다[40]. 더욱이, 여자 고등학생의 운동 종목별 골밀도 연구에서도 태권도, 유도, 역도 종목에 비해 장거리 달리기선수들에서 골밀도가 낮게 나타났다[41]. 이러한 결과를 비추어 볼 때 유산소 운동 트레이닝으로 청소년시기에 골밀도 향상을 도모할 경우 운동 종류의 선택과 운동 강도의 조절이 중요한 요인으로 작용할 것으로 판단된다. 유산소 운동 트레이닝의 한 종목인 수영(10-19세)에서도 같은 연령대의 일반대조군과 비교하여 골밀도가 낮은 것으로 조사되었다[42]. Bellew 등[43]의 연구에서도 수영, 웨이트 리프팅, 축구선수들의 골밀도를 비교하였는데 축구선수들에 비해 수영선수들의 골밀도가 낮은 것으로 나타났다. 이처럼 수영이나 사이클과 같은 체중의 하중이 없는 유산소 운동종목(Non-weight bearing) 뿐만 아니라, 과다하게 오랫동안 달리는 장거리 달리기 또한 청소년기의 골밀도 향상에는 도움이 안될 뿐만 아니라, 반대로 부정적으로 작용할 가능성마저 있을 것으로 판단되어 주의가 필요하다.

5. 핵심 질문5: 청소년기의 최대골량을 높이기 위해서는 어떻게 유산소 운동을 하면 효과적인가?지금까지의 선행연구들에서는 청소년 선수들의 종목별 골밀도 비교와 관련된 논문이 대부분이어서 명확한 운동방법을 제시하는 것에는 한계가 있지만 선행연구들을 중심으로 요약하면 Table 5와 같다. 유산소성 운동 트레이닝은 하루 2시간, 주 5회, 5주간의 운동으로 골 형성 지표들의 증가와 골 흡수 지표들의 감소 효과를 초래하며[35], 육상운동 프로그램을 12주 동안 주 4회 하루 60분, 운동자각도 11-15 강도로 실시하면 골밀도 향상에 효과적인 것으로 제시되고 있어[36], 최소 5주, 주 4회 이상, 하루 60분 정도의 유산소 운동 트레이닝은 골밀도 증가에 효과적일 것으로 판단된다. 또한 유산소 운동과 저항 운동을 동시에 실시하는 복합 운동도 효과적이라고 보고되고 있으며[44], 여자대학생들의 대상으로 한 연구에서도 달리기 집단과 웨이트 트레이닝 집단 모두에서 골밀도에 긍정적으로 작용하는 것으로 나타났다 [45]. 단, 대표적인 Non weight-bearing 종목인 수영과 사이클 선수, 그리고 지구성 달리기 선수들의 경우 골밀도가 낮아질 가능성이 있으므로 각별히 주의를 기울여야 할 것이다.

6. 핵심 질문6: 저항성 운동은 청소년의 골밀도 향상에 효과적인 전략인가?저항성운동은 일반적으로 근력, 근지구력, 파워, 근육 부피 등을 향상 또는 증가시키기 위한 프리 웨이트(Free weight) 또는 웨이트 기구(Weight machines), 탄성밴드(Elastic bands) 등을 이용하여 중량에 저항하는 운동을 말한다. 저항성운동의 구성은 신체 각 관절 부위에 대한 운동의 세트, 반복 횟수, 강도(무게), 휴식 주기 등으로 이루어진다. 1980년대까지만 하더라도 청소년의 저항성운동은 근골격계의 상해 위험이 높다는 이유로 권장되지 않았다[46]. 그러나 그 후 저항성운동의 강도와 세트 그리고 기간이 충분할 경우 청소년의 성숙과 성장뿐만 아니라 근력을 증가시킨다는 것은 많은 연구에 의해 밝혀졌다[46]. 또한, 미국 소비자제품안전위원회(U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission)의 미국 전자부상감시시스템(National Electronic Injury Surveillance System)은 저항성운동과 상해와의 관련성을 조사한 결과, 저항성운동에 따른 손상의 원인은 움직임과 기구와는 관련이 없다는 결론을 내렸다[47]. 대부분의 신체활동과 마찬가지로 청소년을 대상으로한 저항운동은 어느 정도는 근골격계 부상의 위험이 있지만, 이러한 위험은 청소년이 정기적으로 참여하는 다른 많은 스포츠 및 신체활동 보다 크지 않고 그 이점이 크다고 할 수 있다[46]. 따라서 Table 6에 제시된 많은 연구처럼 청소년의 골밀도 향상을 위한 저항성운동은 효과적인 전략일 것이다. 청소년의 골밀도 향상을 위한 저항성운동의 강도는 모든 연구에서 명확히 제시하지는 않았으나, 중강도 이상이 효과적이었다[48-51]. 저항성운동의 양은 저항성운동의 형태에 따라 다르지만, 일반적인 프로그램인 프리 웨이트 운동과 기구가 결합된 경우 주당 90-180분의 운동량에서 효과가 있었으나[10,14,21], Witzke 등[52]에 의하면 주당 90-135분의 운동량에서 효과가 없었기에 주당 180분 이상의 운동량이 요구될 것이다. 저항성운동 기간은 짧게는 12주[48]부터 6-12개월[44,50,53] 그리고 12개월 이상[43,49,51,54]에서 효과적이었다. 따라서 강도와 양에 따라 다소 차이는 있겠지만, 이 두 요소가 충분히 충족된다면 3개월 정도의 저항성운동만으로도 청소년기의 골밀도 향상에는 효과적일 것이다.

7. 핵심 질문7: 어떤 방법의 저항성 운동이 청소년의 최대골량 향상에 도움이 되는가?골량의 경우 성인이 된 이후에는 지속적으로 감소되기 때문에[22] 청소년기에는 성인 이후 발생할 수 있는 골다공증과 취약 골절을 예방하기 위해 최대골량 향상에 따른 골강도(Bone strength)를 향상시킬 필요가 있다. 충분한 최대골량 달성을 위해서는 칼슘 섭취와 체중부하 신체활동이 필수적인데, 이 중 체중부하 신체활동이 더욱 중요한 전략으로 간주된다.[55] 특히 격렬한 점핑(High-impact jumping) 또는 저항성운동은 최대골량을 향상시키는데 더 효과적인 운동방법이다[6]. 그러나 잘못된 저항성운동의 자세와 프로그램의 설계는 상해를 유발할 수 있기 때문에[46] 관심을 가지고 관리해야 할 부분이다. 이를 위한 세 가지의 중요한 관점으로는 올바른 자세로 들어올리기 위한 교육, 적절한 감독, 그리고 효과적인 무게로 들어 올리는 것이다[56]. 따라서 체육을 전공한 교사로부터 학교 수업시간에 이러한 교육과 관리가 이루어진다면 최대골량 향상을 위한 매우 효과적인 방법이 될 것이다. 한편, 웨이트 기구를 이용하는 운동의 경우 장비 구입이 어렵고 정확한 기술 교육이 힘들기 때문에 비교적 따라하기 쉽고 특별한 장비도 필요치 않은 체중의 하중을 이용한 팔굽혀 펴기나 맨몸 스쿼트와 같은 저항성 운동이 좋은 대안이 될 수 있다. 특히, 점핑은 청소년의 골량 향상에 효과적 이고[6,53,57-59], 교육하기에도 비교적 쉬운 운동이기에 청소년기의 최대골량 향상을 위한 좋은 저항성 운동 중 하나로 추천된다.

8. 핵심 질문8: 점프 운동(Jump exercise)은 청소년기의 골밀도 향상에 효과적인가?플라이오매트릭(Plyometric Exercise) 운동은 높은 강도의 운동 형태로 주로 엘리트 선수들이 민첩성, 유연성 혹은 근파워를 증진시키기 위한 목적으로 사용되며 다양한 점프 운동이 포함된다. 두발 모듬 뛰기, 줄넘기와 같은 다양한 형태의 낮은 강도 점프 운동은 청소년기의 근력 특히 하지 근력을 증대시키고 청소년기 골밀도 향상 및 최대골량을 증가시키기 위한 중요한 운동 전략 중 하나로 보고된다[60-65]. Week 등[52]의 연구에 의하면 정규 수업이 시작하기 전 10분씩 주 2회 점프 운동을 8개월간 중재했더니 여자 청소년의 경우 골반과 요추의 골밀도가 점프 운동을 하지 않은 대조군에 비해 증가하는 것으로 나타났고, Witzke & Snow [60] 연구에 의하면 저항성 운동과 플라이오매트릭 운동을 하루 30-45분 주 3회 9개월간 중재 한 결과 전신(Total body)과 요추, 대퇴의 골밀도가 높아진 것으로 확인되었다. 운동선수의 경우 지면으로부터 받는 충격이 큰 운동을 한 선수들이 싸이클링 혹은 수영과 같이 지면으로부터 받는 충격이 적은 운동을 한 선수들에 비해 전신 혹은 요추의 골밀도가 높은 것으로 나타났다[66]. 또한, 여학생들을 대상으로 9개월간 점프 운동을 중재 했을 때 점프 운동을 하지 않은 그룹에 비해 요추의 골밀도가 증가된 것으로 나타났고, 20개월 후 추적 검사를 실시했을 때에도 증가된 요추 골밀도가 유지된 것을 확인하였다[67]. 선행연구들을 종합하여 볼 때 플라이오매트릭 또는 점프 운동은 청소년기 골밀도를 향상시키는데 중요한 운동 형태라 사료될 뿐만 아니라, 점프 운동을 통한 청소년기의 최대골량의 증가는 노인기 골다공증을 예방할 수 있을 것으로 사료된다.

9. 핵심 질문9: 청소년기의 최대골량을 높이기 위해서는 어떻게 점프 운동을 하면 효과적인가?현재까지 청소년기 골밀도를 높이기 위한 점핑 운동 처방 전략에 관한 정확한 운동 방법은 제시되어 있지 않지만 선행연구를 요약해보면 Table 7과 같다. 점핑 운동 중재 기간은 16주에서 2년까지 다양하게 청소년을 대상으로 시도되었다. 16주간 유산소성 운동에 점프 운동을 복합 처치한 경우 골형성과 관련된 지표들이 혈중에서 증가한 것을 확인하였기에 최소 16주 이상의 점핑 운동을 중재하는 것이 골밀도를 변화시키기에 가능한 기간이라 사료된다[68]. 또한 정규 체육수업을 시작하기 전 10분 가량의 점프 운동을 주 2회 8개월간 지속했을 시에도 남녀 청소년들의 골밀도가 증가되었고, 하루 45분 주 3회 9개월 이상 유산소성 운동 혹은 저항성 운동에 점프 운동을 복합 처치 했을 경우에도 하지의 골밀도가 증가된 것으로 나타났다[52,60]. 즉, 박스 점프혹은 줄넘기와 같은 점프 운동을 최소 주 2회 10분가량 9개월가량 지속하는 것만으로도 골밀도를 증가시키기에 충분한 운동량으로 간주된다. 그러나 높은 상자를 이용한 점프 운동을 수행할 시에는 상해의 위험이 있기 때문에 청소년의 경우 줄넘기, 점프, 홈(Hop)과 같은 낮은 수준의 운동 강도를 선택하기를 권장한다.

DISCUSSION본 운동 가이드라인 개발의 목적은 청소년들의 최대골량을 높이기 위한 근거 기반의 운동방법을 제시하는 것이다. 이를 통하여 미래 고령사회의 골다공증 및 골절 발생율을 낮추어 국민건강에 이바지 할 수 있을 것이다. 이 가이드라인의 주요 의미는 청소년들의 골밀도 증가에 영향을 미치는 다양한 운동 방법과 그 효과를 이해하고, 운동 형태와 빈도, 강도, 시간을 잘 조절하여 청소년들에게 운동을 지도해야 한다는 것이다. 이 가이드라인을 개발하기 위해 대한골대사학회와 한국 운동생리학회는 공동으로 운동위원회를 구성하였다. 이 위원회는 체계적인 문헌 검토를 통하여 운동위원회의 일치된 의견으로 근거 수준평가(The level of evidence)와 권장 수준 평가(The grade of recommendation)기준에 기반한 운동 효과를 판정하고, 효과적인 운동방법을 선정하여 운동 가이드라인을 채택하였다. 최종 선정된 청소년들의 최대골량을 높이기 위한 운동 가이드라인을 Table 8에 나타냈다. 이 가이드라인은 5-6개월 이상 격렬한 신체활동을 권장하며, 격렬한 신체활동은 저항성 운동과 점프 운동을 포함할 것을 권장한다. 저항성 운동은 프리 웨이트 또는 웨이트 기구을 복합한 운동 형태로, 8개 이상의 대 근육근을 사용하여, 한 부위 별로 1-2세트, 한 세트 당 10-12회 반복하는 강도로, 1주일에 3일정도 운동하는 것을 권장한다. 점프 운동은 플라이오 매트릭 혹은 줄넘기 등의 운동을 1분에 50회 실시하는 강도로, 1일 최소 10분 이상, 1주일에 2일 이상 운동하는 것을 권장한다(Fig. 2). 그러나 유산소 운동은 수영과 지구성 달리기와 같은 경우 일부 연구에서 골밀도 증가에 부정적인 효과도 보고되고 있어, 확인 연구를 진행하면 제시된 결과가 변할 가능성 있고 효과에 대한 근거는 약간 미흡 하므로 선택적으로 권장하는 것으로 하였다.

최근 각국에서 뼈 건강유지 및 증진을 위한 다양한 운동 가이드라인이 제시되고 있다. Exercise and Sports Science Australia (ESSA)가 발표한 position statement on exercise prescription for the prevention and management of osteoporosis는 대상자를 저위험 집단(Low-risk individuals), 중위험 집단(Moderate-risk individuals), 고위험 집단(High-risk individuals)으로 나누고, 각각의 집단에게 체중부하 운동과 점진적인 저항성 운동(Progressive resistance training), 밸런스 운동(Balance training)을 권장하고 있다[23]. 또한 다국적의 연구자가 발표한 가이드라인에서는[17] 골다공증이 있는 노인과 골다공증성 척추 골절 환자에게 저항성 운동과 밸런스 운동이 포함된 다양한 운동 프로그램을 권장하고 있다. 이들 논문은 골다공증을 예방하고자 하는 일반 성인이나 골감소증 환자를 대상으로 한 운동 가이드라인으로 성장기에 있는 청소년들에게 적용하기에는 미흡한 면이 있다[16]. 최근 미국 보건복지부(U.S. Department of Health and Human Services)가 발표한 The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans [19]에서는 다양한 연령층에 대한 신체활동 가이드라인을 발표하면서, 6세에서 17세 사이 아동과 청소년들에게 하루 최소 한시간 혹은 그 이상의 중-고강도 신체활동을 권장하였다. 특히, 1주일에 매일 또는 최소 3일 이상의 신체활동이 반드시 포함되어야 한다고 권고하고 있는 것은 주목할 점이다. 그러나 이 가이드라인은 전반적인 국민 건강에 초점이 맞춰진 것으로 운동과 골밀도에 대한 구체적인 연구를 통하여 도출된 결과라 보기 어렵다. 또한, 아동과 청소년의 구분이 없고, 빈도(F), 강도(I), 형태(T), 시간(T)등의 구체적인 운동 방법은 제시되지 않고 있다. 이러한 가이드라인에 비교하여 우리들의 청소년들의 최대골량을 높이기 위한 운동 가이드라인은 골밀도 증가에 영향을 미치는 다양한 운동방법을 종합적으로 검토하여 그 결과를 집약한 것이 큰 차별점이며, 13-18세까지의 청소년을 대상으로 운동 가이드라인을 제시하는 것이 특징이라 하겠다.

한편, 교육부의 ‘2018년도 학생 건강 검사 표본 통계 분석결과’에 따르면, 남녀 중고등학생의 체중과 신장은 점점 증가하여 체격은 향상되었지만, 일주일에 3일 이상 격렬한 신체활동을 하는 학생 비율은 중학생 35.08%, 고등학생 23.60%로 저조하였으며, 5일 이상하는 학생의 비율은 각각 14.59%, 9.69%로 매우 저조한 것으로 밝혀졌다[69]. 이와 더불어 우리나라 10대 청소년들의 근력, 근지구력, 순발력을 포함한 체력수준이 지난 10년 동안 지속적으로 감소한 것으로 보고되고 있다[70]. 세계적으로도 청소년의 체력은 감소하고 있고, 11-17세 청소년의 81%가 일일 최소 1시간 이상의 신체활동에도 참여하지 않는다고 보고되고 있다[71]. 더구나, 우리나라 중·고교 학생들의 체육 및 건강에 대한 학습시간 비율은 약 8%로 OECD국가 평균 비율 7%에 비해 약간 높은 수치이지만, 10% 대인 일본, 캐나다, 프랑스와 같은 선진국들과 비교했을 때 체육 및 건강에 대한 학습시간이 낮은 편이다[72]. 더욱이 학교체육시간 중 실질적으로 운동한 시간에 대한 조사에서는 일주일에 학교체육시간 중 ‘땀 흘려 운동한 시간이 1시간 이하’ 라고 응답한 비율이 중·고교 평균 43.0%이고 남학생보다 여학생에서 운동 참여 비율이 현저하게 떨어지는 것으로 보고하였다[73]. 아마 정확한 조사는 이루어지지 않았지만, 대학 입시를 앞둔 고등학교 2, 3학년의 경우, 몇 시간 안 되는 체육시간 마저 영어, 수학 등의 교과목으로 대치되는 것을 감안하면, 청소년들의 운동 참여율은 매우 심각한 수준일 것이라고 생각된다. 이처럼 우리나라 청소년들은 신체활동 참여율이 떨어져 전반적인 체력 수준이 감소하고 있으며, 선진국과 비교하여 부족한 학교 체육 시간조차도 열심히 운동을 하지 않는 것이 현실인 것이다.

이 연구를 통하여 저항성 운동과 점프 운동을 포함한 격렬한 신체활동이 청소년들의 골밀도를 증가시켜 최대골량을 향상시키는 것이 밝혀 졌으므로, 운동 가이드라인에 제시된 격렬한 신체활동을 적극적으로 실천하는 노력이 필요할 것이다. 이를 위하여 침체되어 있는 학교 교육현장의 체육시간을 활성화하고, 가이드라인에 제시된 운동을 체계적으로 시스템화하여 적용하여야 할 것이다. 또한 교육부에서도 매년 실시하고 있는 학생 건강 검사 표본 통계 분석에 골밀도를 포함시켜 비만율과 같이 관리 된다면, 학생들이 더욱 적극적으로 격렬한 신체활동을 해야할 이유를 쉽게 찾을 수 있을 것이다. 이를 통하여 우리나라 청소년들의 최대골량이 증가된다면, 이들이 자라서 성인이 되고, 노인이 되었을 때 우리나라 국민의 전반적인 건강 증진에 크게 기여할 것으로 사료된다.

이 운동 가이드라인을 개발하며 인종의 차이를 반영하기 위하여 우리나라를 포함한 적어도 아시안 청소년들의 연구 결과를 기반으로 검토를 계획하였다. 그러나 논문의 절대적인 부족으로 미국과 유럽을 포함한 다수의 인종이 포함된 연구가 대상이 되었기에 우리나라 청소년으로 국한하기에는 제한이 있다. 또한, 칼슘 섭취를 고려한 논문과 고려하지 않은 논문이 혼재되어 있으며, 골밀도 평가에 있어서도 다양한 장비가 이용된 점도 연구의 제한점이라 할 수 있다.

Fig. 1.Fig. 1.Flowchart of the systematic search of literature and selection process for the development of guideline for adolescents.

Fig. 2.Fig. 2.Exercise guidelines for increasing peak bone mass (PBM) in adolescence. VPA, vigorous physical activity.

Table 1.Key questions for determining exercise guidelines Table 2.The level of evidence in the literature Table 3.The grade of recommendations to exercise guideline Table 4.Physical activity studies on bone health in adolescents

Table 5.Aerobic endurance exercise training studies on bone health in adolescents.

INT, intervention; FITT, frequency, intensity, time, type; BMD, bone mineral density; BMC, bone mineral content; WB, whole body; FN, femoral neck; L, lumbar; LS, lumbar spine; Ca, calcium; EX, exercise; CON, control; AT, aerobic training; BSAP, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase; PICP, C-terminal procollagen peptide; NTX, N-terminal telopeptide cross-links. Table 6.Resistance training studies on bone health in adolescents

Table 7.A description of power (plyometric) exercise studies on bone health in adolescents.

FITT, frequency, intensity, time, type; RCT, randomized controlled trial; INT, intervention study; M/F, male/female; CON, control; EX, exercise; RT, resistance training; AT, aerobic training; BMD, bone mineral density; BMC, bone mineral content; WB, whole body; PF, proximal femur; LS, lumbar spine; FN, femoral neck; TD, tibia diaphysis. Table 8.Exercise guidelines based on FITT for increasing peak bone mass in adolescents. REFERENCES1. Duncan CS, Blimkie CJ, Cowell CT, Burke ST, Briody JN, et al. Bone mineral density in adolescent female athletes: relationship to exercise type and muscle strength. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:286-94.

2. LeBlanc AD, Spector ER, Evans HJ, Sibonga JD. Skeletal responses to space flight and the bed rest analog: a review. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2007;7:33-47.

3. Warden SJ, Hurst JA, Sanders MS, Turner CH, Burr DB, et al. Bone adaptation to a mechanical loading program significantly increases skeletal fatigue resistance. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:809-16.

4. Krahl H, Michaelis U, Pieper HG, Quack G, Montag M. Stimulation of bone growth through sports. A radiologic investigation of the upper extremities in professional tennis players. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:751-7.

5. Office of the Surgeon General. Bone health and osteoporosis: A report of the surgeon general. Rockville, MD: Office of the Surgeon General 2004.

6. Kohrt WM, Bloomfield SA, Little KD, Nelson ME, Yingling VR, et al. American college of sports medicine position stand: physical activity and bone health. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:1985-96.

7. Heaney RP, Abrams S, Dawson-Hughes B, Looker A, Marcus R, et al. Peak bone mass. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:985-1009.

8. Hernandez CJ, Beaupré GS, Carter DR. A theoretical analysis of the relative influences of peak BMD, age-related bone loss and menopause on the development of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:843-7.

9. Clark EM, Ness AR, Bishop NJ, Tobias JH. Association between bone mass and fractures in children: a prospective cohort study. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1489-95.

10. Baptista F, Janz KF. Habitual physical activity and bone growth and development in children and adolescents: A public health perspective. In: Preedy VR, editor. Handbook of growth and growth monitoring in health and disease. New York, NY: Springer 2011;(pp. 2395-411).

11. Gunter KB, Almstedt HC, Janz KF. Physical activity in childhood may be the key to optimizing lifespan skeletal health. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2012;40:13-21.

12. Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Mâsse LC, Tilert T, et al. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:181-8.

13. Ministry of Education; Ministry of Health and Welfare; Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The twelfth Korea youth risk behavior web-based survey. Sejong: Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016.

14. National Youth Policy Institute. Study on the current status of Korean children’s and youth rights III. Sejong: National Youth Policy Institute 2013.

15. Kim S, Jee S, Lee S, Park J, et al. Guidance for development of clinical practice guidelines. National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency 2011;(pp. 20-77).

16. Giangregorio LM, Papaioannou A, Macintyre NJ, Ashe MC, Heinonen A, et al. Too Fit To Fracture: exercise recommendations for individuals with osteoporosis or osteoporotic vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:821-35.

17. Beck BR, Daly RM, Singh MA, Taaffe DR. Exercise and sports science Australia (ESSA) position statement on exercise prescription for the prevention and management of osteoporosis. J Sci Med Sport. 2017;20:438-45.

18. Janz KF, Thomas DQ, Ford MA, Williams SM. Top 10 research questions related to physical activity and bone health in children and adolescents. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2015;86:5-12.

19. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical activity guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed., Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.

20. In JPT Higgins, S Green (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: Version 5.1.0. London, UK: The Cochrane Collaboration 2011.

21. Bailey DA, McKay HA, Mirwald RL, Crocker PR, Faulkner RA. A sixyear longitudinal study of the relationship of physical activity to bone mineral accrual in growing children: the university of Saskatchewan bone mineral accrual study. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1672-9.

22. Baxter-Jones AD, Faulkner RA, Forwood MR, Mirwald RL, Bailey DA. Bone mineral accrual from 8 to 30 years of age: an estimation of peak bone mass. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1729-39.

23. Berger C, Goltzman D, Langsetmo L, Joseph L, Jackson S, et al. Peak bone mass from longitudinal data: implications for the prevalence, pathophysiology, and diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:1948-57.

24. Weaver CM, Gordon CM, Janz KF, Kalkwarf HJ, Lappe JM. Erratum to: The National Osteoporosis Foundation’s position statement on peak bone mass development and lifestyle factors: a systematic review and implementation recommendations. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27:1387.

25. Tveit M, Rosengren BE, Nilsson JÅ, Karlsson MK. Exercise in youth: High bone mass, large bone size, and low fracture risk in old age. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25:453-61.

26. Strope MA, Nigh P, Carter MI, Lin N, Jiang J, et al. Physical activityassociated bone loading during adolescence and young adult hood is positively associated with adult bone mineral density in men. Am J Mens Health. 2015;9:442-50.

27. Bielemann RM, Domingues MR, Horta BL, Menezes AM, Gonçalves H, et al. Physical activity throughout adolescence and bone mineral density in early adulthood: the 1993 Pelotas (Brazil) Birth Cohort Study. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:2007-15.

28. Tolonen S, Sievanen H, Mikkilä V, Telama R, Oikonen M, et al. Adolescence physical activity is associated with higher tibial pQCT bone values in adulthood after 28-years of follow-up--the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study Bone. 2015;75:77-83.

29. Jackowski SA, Kontulainen SA, Cooper DM, Lanovaz JL, Beck TJ, et al. Adolescent physical activity and bone strength at the proximal femur in adulthood. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46:736-44.

30. Ramires VV, Dumith SC, Wehrmeister FC, et al. Physical activity throughout adolescence and body composition at 18 years: 1993 Pelotas (Brazil) birth cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:105.

31. Duckham RL, Baxter-Jones AD, Johnston JD, Hallal PC, Menezes AM, et al. Does physical activity in adolescence have site-specific and sex-specific benefits on young adult bone size, content, and estimated strength? J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:479-86.

32. Marin-Puyalto J, Mäestu J, Gómez-Cabello A, Lätt E, Remmel L, et al. Frequency and duration of vigorous physical activity bouts are associated with adolescent boys’ bone mineral status: A cross-sectional study. Bone. 2019;120:141-7.

33. Nordström P, Pettersson U, Lorentzon R. Type of physical activity, muscle strength, and pubertal stage as determinants of bone mineral density and bone area in adolescent boys. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:1141-8.

34. Diniz TA, Agostinete RR, Costa PJ, Saraiva BTC, Sonvenso DK. Relationship between total and segmental bone mineral density and different domains of physical activity among children and adolescents: cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J. 2017;135:444-9.

35. Eliakim A, Raisz LG, Brasel JA, Cooper DM. Evidence for increased bone formation following a brief endurance-type training intervention in adolescent males. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1708-13.

36. Im KC. Effects of athletics exercise program on the health-related fitness, abdominal fat area and bone mineral density in middle school girls. Korea J Sports Sci. 2016;25:1337-46.

37. Okano H, Mizunuma H, Soda M, Matsui H, Aoki I, et al. Effects of exercise and amenorrhea on bone mineral density in teenage runners. Endocr J. 1995;42:271-6.

38. Jang JH. Comparison of upper limb bone density between high school women soccer players and age-matched women students. Korea J Sport. 2008;6:167-75.

39. Burrows M, Nevill AM, Bird S, Simpson D. Physiological factors associated with low bone mineral density in female endurance runners. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37:67-71.

40. Nguyen T, Sambrook P, Kelly P, Jones G, Lord S, et al. Prediction of osteoporotic fractures by postural instability and bone density. BMJ. 1993;307:1111-5.

41. Lee CD, Kang HY, Oh DJ, Choi HJ, Byun WW, et al. Bone mineral density in different types of sports: Female high school athletes. J Korean Phys Educ Assoc Girls Women. 2006;20:37-44.

42. Agostinete RR, Maillane-Vanegas S, Lynch KR, Turi-Lynch B, Coelho-E-Silva MJ, et al. The impact of training load on bone mineral density of adolescent swimmers: A structural equation modeling approach. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2017;29:520-8.

43. Bellew JW, Gehrig L. A comparison of bone mineral density in adolescent female swimmers, soccer players, and weight lifters. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2006;18:19-22.

44. Campos RM, de Mello MT, Tock L, Silva PL, Masquio DC, et al. Aerobic plus resistance training improves bone metabolism and inflammation in adolescents who are obese. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28:758-66.

45. Snow-Harter C, Bouxsein ML, Lewis BT, Carter DR, Marcus R. Effects of resistance and endurance exercise on bone mineral status of young women: a randomized exercise intervention trial. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:761-9.

46. Faigenbaum AD, Kraemer WJ, Blimkie CJ, Jeffreys I, Micheli LJ. Youth resistance training: updated position statement paper from the national strength and conditioning association. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23:S60-79.

47. United States Consumer Product Safety Commission. National electronic injury surveillance system. Washington, DC: United States Consumer Product Safety Commission 1987.

48. Volek JS, Gómez AL, Scheett TP, Sharman MJ, French DN, et al. Increasing fluid milk favorably affects bone mineral density responses to resistance training in adolescent boys. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:1353-6.

49. Nichols DL, Sanborn CF, Love AM. Resistance training and bone mineral density in adolescent females. J Pediatr. 2001;139:494-500.

50. Bernardoni B, Thein-Nissenbaum J, Fast J, Day M, Li Q, et al. A school-based resistance intervention improves skeletal growth in adolescent females. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:1025-32.

51. Koşar ŞN. Associations of lean and fat mass measures with whole body bone mineral content and bone mineral density in female adolescent weightlifters and swimmers. Turk J Pediatr. 2016;58:79-85.

52. Weeks BK, Young CM, Beck BR. Eight months of regular in-school jumping improves indices of bone strength in adolescent boys and Girls: the POWER PE study. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1002-11.

53. Stear SJ, Prentice A, Jones SC, Cole T. Effect of a calcium and exercise intervention on the bone mineral status of 16-18-y-old adolescent girls. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:985-92.

54. Welten DC, Kemper HC, Post GB, Van Mechelen W, Twisk J, et al. Weight-bearing activity during youth is a more important factor for peak bone mass than calcium intake. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:1089-96.

55. Myers AM, Beam NW, Fakhoury JD. Resistance training for children and adolescents. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:137-43.

56. Vlachopoulos D, Barker AR, Ubago-Guisado E, Williams CA, Gracia-Marco L. The effect of a high-impact jumping intervention on bone mass, bone stiffness and fitness parameters in adolescent athletes. Arch Osteoporos. 2018;13:128.

57. Vlachopoulos D, Barker AR, Ubago-Guisado E, Williams CA, Gracia-Marco L. A 9- month jumping intervention to improve bone geometry in adolescent male athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50:2544-54.

58. MacKelvie KJ, McKay HA, Petit MA, Moran O, Khan KM. Bone mineral response to a 7-month randomized controlled, school-based jumping intervention in 121 prepubertal boys: associations with ethnicity and body mass index. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:834-44.

59. Larsen MN, Nielsen CM, Helge EW, Madsen M, Manniche V, et al. Positive effects on bone mineralisation and muscular fitness after 10 months of intense school-based physical training for children aged 8-10 years: the FIT FIRST randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:254-60.

60. Witzke KA, Snow CM. Effects of plyometric jump training on bone mass in adolescent girls. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:1051-7.

61. Dekker J, Nelson K, Kurgan N, Falk B, Josse A, et al. Wnt signaling-related osteokines and transforming growth factors before and after a single bout of plyometric exercise in child and adolescent females. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2017;29:504-12.

62. Arnett MG, Lutz B. Effects of rope-jump training on the os calcis stiffness index of postpubescent girls. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:1913-9.

63. Johannsen N, Binkley T, Englert V, Neiderauer G, Specker B. Bone response to jumping is site-specific in children: a randomized trial. Bone. 2003;33:533-9.

64. Heinonen A, Sievanen H, Kannus P, Oja P, Pasanen M, et al. High-impact exercise and bones of growing girls: a 9-month controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:1010-7.

65. Pettersson U, Nordström P, Alfredson H, Henriksson-Larsén K, Lorentzon R. Effect of high impact activity on bone mass and size in adolescent females: A comparative study between two different types of sports. Calcif Tissue Int. 2000;67:207-14.

66. Dias Quiterio AL, Carnero EA, Baptista FM, Sardinha LB. Skeletal mass in adolescent male athletes and nonathletes: relationships with high-impact sports. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25:3439-47.

67. Kontulainen SA, Kannus PA, Pasanen ME, Sievänen HT, Heinonen AO, et al. Does previous participation in high-impact training result in residual bone gain in growing girls? One year follow-up of a 9-month jumping intervention. Int J Sports Med. 2002;23:575-81.

68. Evans RK, Antczak AJ, Lester M, Yanovich R, Israeli E, et al. Effects of a 4-month recruit training program on markers of bone metabolism. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:S660-70.

69. Ministry of Education. Sampling design of student health examinations in 2018. 2019 [cited by 2019 May 1]. Available from: https://www.moe.go.kr/boardCnts/view.do?boardID=294&boardSeq=77144&lev=0&m=02.

70. Ministry of Culture. Sports and Tourism. Survey on citizens’ sports participation. Seoul: Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism 2015.

71. World Health Organization. Prevalence of insufficient physical activity. Geneva, CH: World Health Organization 2010.

72. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Education at a glance 2015: OECD indicator. Paris, FR: OECD Publishing 2015.

National Youth Policy Institure. NYPI panel survey: Junior high school; 2010;[cited by 2011 Aug 1]. Available from: https://www.nypi.re.kr/archive/brdartcl/boardarticleList.do?brd_id=BDIDX_3A94C7B4Y1bY00jGQSP1xB&menu_nix=tli3O5c4&srch_mu_lang=ENG.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||