마른 비만의 대사 및 심혈관계 질환 위험성과 선제적 예방을 위한 운동 중재

Cardiometabolic Disease Risk in Normal Weight Obesity and Exercise Interventions for Proactive Prevention

Article information

Trans Abstract

PURPOSE

Normal weight obesity (NWO) is characterized by a normal body mass index but a high body fat mass percentage and low skeletal muscle mass, thereby increasing the risk of cardiometabolic dysfunction and morbidity. However, the effects of exercise intervention in reducing the risk of cardiometabolic disease in NWO have not been fully elucidated. Therefore, this review aimed to summarize the potential cardiometabolic disease risk and to provide implications of exercise interventions for the proactive prevention of cardiometabolic disease risk in NWO.

METHODS

We searched and summarized the literature on the cardiometabolic risk factors in NWO. In addition, we summarized literature investigating the effects of exercise intervention on the cardiometabolic risk factors in NWO. We performed the literature search using PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases.

RESULTS

NWO was associated with increased visceral fat, ectopic fat, oxidative stress, inflammatory cytokines, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and subclinical atherosclerosis compared with normal weight lean. NWO requires exercise interventions that induce alterations in body composition, such as decreased body fat percentage and increased muscle mass. Resistance exercise (RE) and high-intensity interval exercise (HIIE) can improve lipid components and alter body composition in NWO. In addition, low-intensity blood flow restriction resistance exercise (BFR-RE) may enhance muscular strength and anaerobic power in NWO.

CONCLUSIONS

The cardiometabolic disease risk is increased in NWO. We suggest that exercise interventions (RE, HIIE, and BFR-RE) may effectively prevent cardiometabolic disease risk and alter body composition in NWO. As this has potential implications for exercise interventions in NWO, further investigations are needed to find the optimal exercise for proactive prevention of cardiometabolic risk in NWO.

서 론

비만(obesity)은 인슐린 저항성(insulin resistance), 이상지질혈증(dyslipidemia), 제2형 당뇨병(type 2 diabetes mellitus), 심혈관계 질환(cardiovascular disease) 등의 심각한 합병증의 주요 위험요인이며, 각종 질환 발병을 초래하고 사망률을 높인다[1–3]. 비만 진단은 체질량지수(body mass index, BMI)로 용이하게 측정 가능하며, BMI는 단순성(simplicity) 및 재현성(reproducibility) 등 장점이 존재하여 임상에서 많이 사용하지만, 체지방량 및 근육량과 같은 신체조성을 구별할 수 없기 때문에 비만 진단을 위한 최적의 방법이 아닐 수 있다[4]. 즉, BMI는 신체조성을 반영하지 않기에 체지방률이 낮고 근육량이 많은 개인을 비만으로 과대평가하거나, 반대로 체지방률은 비만에 속하지만 근육량이 적은 개인을 과소평가하는 등 비만 진단의 타당성에 문제가 발생하기도 한다[5–7]. 이러한 BMI의 제한점으로 인해 BMI 수치가 18.5-25 kg/m2로 정상 범위에 속하지만, 근육량은 적고 체지방률이 비만에 해당되는 비교적 새로운 비만의 범주인 마른 비만(normal weight obesity)의 문제가 최근 부각되고 있다[8,9].

마른 비만은 BMI가 정상 범위에 속하는 것과 동시에 체지방률이 높은 것으로 정의된다[9–11]. 마른 비만을 정의하기 위한 BMI의 정상 범위는 18.5-25 kg/m2 로 비교적 명확히 설정되어 있는 것에 반해, 체지방률의 기준(cutoff)은 선행연구에 따라 다르며 명확히 설정되어 있지 않다. 선행연구에서는 마른 비만을 분류하기 위해서 연구 대상자 중 체지방률이 상위 3분위수(tertile), 4분위수(quartile) 또는 90%에 해당되는 대상자를 마른 비만으로 정의하는 경우가 있으며[12–15], 특정 체지방률 기준을 설정하여 마른 비만을 정의하는 경우도 있다[11,16,17]. 백분위 활용 및 특정 체지방률 기준을 설정하여 마른 비만을 정의한 선행연구들에 의하면, 마른 비만 남성에 대한 체지방률 기준은 최소 17.6%부터 최대 32.6%까지(17.6–32.6%) 다양하며[18,19], 마른 비만 여성에 대한 체지방률 기준도 28–44.4%로 다양하다[16,19]. 현재까지 마른 비만의 진단 기준에 대해 명확하게 설정되어 있지는 않지만, 선행연구에서 마른 비만 여성을 대상으로 가장 많이 사용하는 체지방률 기준은 30%로 판단된다[11,17,20-22].

전 세계 성인 중 마른 비만 유병률은 약 4.5-22%로 추정된다[9]. 성별에 따른 마른 비만 유병률을 보았을 때, 남성의 경우 3% 미만, 여성의 경우는 남성보다 약 20배까지 높은 유병률(2-28%)을 나타내는 것으로 보고되었다[6,13,23]. 대한민국의 경우, 2009-2010년 국민건강영양조사에 의하면 정상 BMI를 가진 성인 여성 중 마른 비만에 노출되어 있는 여성은 약 30%로 추정된다[24]. 이와 같은 유병률을 나타내는 마른 비만은 중 ∙노년뿐만 아니라, 청소년 및 젊은 성인에서도 빈번하게 나타난다[25–27]. 전 연령층에서 빈번하게 나타나는 마른 비만은 성별, 인종, 유전, 식이 습관, 신체활동 부족 등의 병인학적 요인(etiological factors)으로 인해 나타날 가능성이 존재하지만[18,22,28-31], 현재까지 마른 비만의 발생 원인은 명확히 밝혀지지 않았다[9].

일반적인 비만과 마른 비만의 가장 큰 차이점은 마른 비만의 경우 일반 비만인에 비해 상대적으로 적은 골격근육량(skeletal muscle mass)을 가지고 있다는 점이다[32]. 이러한 점을 고려했을 때, 골격근육량이 최고점인 20대 젊은 연령부터 마른 비만과 같은 신체조성을 가지고 있을 경우 근감소성 비만(sarcopenic obesity)에 노출될 가능성이 높으며, 이로 인해 제2형 당뇨병 및 심혈관계 질환과 같은 만성질환의 위험성이 증가한다[8,33–35]. 또한 마른 비만인은 체지방률이 비만에 속하는 특징을 가지고 있어 중성지방(triglycerides, TG)이 높고, 대사증후군(metabolic syndrome) 발병 위험성도 높아진다[24,36]. 즉, 마른 비만자는 일반 비만자와 유사한 질환 합병증 위험성을 가지고 있지만, 외형상 비만으로 보이지 않기에 질환에 대한 위험성을 인지하지 못한다는 점에서 그 심각성이 존재한다[11,37].

마른 비만으로 인한 병태생리학적 기전과 대사 및 심혈관 질환(cardiometabolic disease)의 위험성에 관한 연구들은 최근까지 활발히 진행되고 있다[9,26,37,38]. 마른 비만은 향후 잠재적인 대사 및 심혈관 질환의 위험성을 가지고 있기 때문에, 마른 비만을 선별하여 적절한 중재를 처치하는 것은 근감소성 비만과 대사 및 심혈관 질환으로의 전이를 막을 수 있는 중요한 선제적 예방(proactive prevention)이 될 수 있다. 비약물적 전략(non-drug strategy) 중 운동(exercise)은 각종 만성질환의 예방 및 개선을 위한 효과적인 방법이다[39–41]. 하지만, 마른 비만의 신체적 특성을 고려하여 예방적 차원의 적절한 운동 중재 방법 설정에 관한 연구는 매우 부족한 실정이다. 따라서 본 종설(review)에서는 1) 마른 비만의 대사 및 심혈관 질환 위험성에 관한 선행연구를 검토하고, 2) 질환의 선제적 예방을 위한 운동 중재 방법에 관한 선행연구의 결과 분석을 통해 마른 비만자를 위한 효과적인 운동 중재 방법을 고찰하며, 3) 이를 통해 향후 진행될 마른 비만자를 위한 예방적 차원의 효과적인 운동 중재 발굴에 대한 시사점을 제공하고자 한다.

연구 방법

1. 자료 검색 및 수집

본 종설에서는 자료 수집을 위해 2000년 1월부터 2022년 6월까지 출판된 문헌들을 학술 검색 시스템인 ‘ PubMed’, ‘ Web of science’, ‘ Google Scholar’를 이용하여 문헌을 검색하였다. 검색은 ‘ normal weight obesity or normal weight obese’, ‘ cardiovascular risk or cardiometabolic risk’, ‘ exercise or training’ 등의 키워드들을 조합하여 문헌 조사를 실시하였다. 마른 비만에 대한 정의 및 진단 기준이 선행연구에 따라 다르게 제시되어, 본 종설에서는 BMI가 18.5-25 kg/m2로 정상 범위에 속하는 것과 동시에 특정 체지방률 기준을 사용하여 마른 비만의 진단 기준을 명확히 제시한 문헌만 포함하였다. 또한 본 종설에서는 마른 비만의 질환 위험성을 조사한 선행 문헌들을 요약 및 검토하기 위해 횡단연구(cross-sectional study), 종단연구(longitudinal study), 사례 대조군 연구(case-control study)를 포함하였으며, 마른 비만을 대상으로 운동 중재에 대한 효과 검토를 위해서 무작위 교차(randomized crossover) 및 무작위 대조 시험(randomized controlled trial)으로 진행한 문헌들을 포함하였다. 자료 수집 과정에서 ‘ metabolically healthy obese’, ‘ metabolically unhealthy obese’와 같은 비만 표현형(phenotype), 그리고 마른 비만이 아닌 ‘ metabolically healthy normal weight’, ‘ metabolically obese but normal weight’, ‘ normal weight with central obesity’와 같은 정상 체중의 다른 표현형은 본 종설의 범위를 벗어나므로 제외하였다.

결 과

1. 마른 비만의 생리적 특성과 대사 및 심혈관계 질환 위험성

마른 비만은 신체적 특징으로 인하여 간혹 “ fat mass disease”로 불리우기도 한다[8]. 마른 비만 집단은 정상 BMI와 체지방률을 가진 집단 보다 근력(muscular strength) 및 골격근육량이 적으며[24,26], 내장지방(visceral fat)이 많고, 간과 근육에 이소성 지방(ectopic fat)이 많이 분포되어 있는 특징이 있다[42,43]. 특히, 이소성 지방의 축적은 지방독성(lipotoxicity)을 유발하여 대사 및 심혈관계 질환을 포함한 여러 만성 질환 발병의 주요 위험 요인으로 작용한다[44]. 또한 이러한 신체적 특성으로 인해 마른 비만 집단은 산화 스트레스(oxidative stress) 및 in-terleukin (IL)-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) 등 염증성 사이토카인(inflammatory cytokine) 수치가 정상 BMI와 체지방률을 가진 집단 보다 높은 특징을 가지고 있다[17,21]. 선행연구에 따르면 마른 비만 집단은 정상 BMI와 체지방률을 가진 집단에 비해 관상동맥질환(coronary artery disease)의 독립적 위험인자인 고밀도지단백질 콜레스테롤(high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL-C)은 낮고, 저밀도지단백질 콜레스테롤(low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C) 및 TG가 높은 특징을 가지고 있다[36,42,45]. 혈중 HDL-C이 낮고, LDL-C 수치가 높으면 활성산소종(reactive oxygen species)에 반응하여 oxidized LDL이 생성되며[46], 이는 혈관내피세포(vascular endothelial cell) 손상과 대식세포(macrophage)에 지질 축적으로 인한 거품세포(foam cell) 형성을 통해 지방선조(fatty streak)를 유발하고, 이로 인해 섬유성 플라크(fibrous plaques)를 형성해 죽상동맥경화증(atherosclerosis)을 유발할 수 있다[47]. 실제로 Kim et al. [42]의 연구에 의하면 마른 비만 집단은 정상 BMI와 체지방률을 가진 집단 보다 HDL-C은 낮고, 혈압, TG, LDL-C, 동맥경직도 및 관상동맥 내 연성 플라크(soft plaques)가 높아 무증상 죽상동맥경화증(subclinical atherosclerosis)의 가능성이 있어 잠재적으로 관상동맥질환의 높은 발병 위험성이 있는 것으로 보고되었다.

또한 앞서 언급했듯 마른 비만은 체지방률이 높을 뿐만 아니라, 근력 및 골격근육량이 낮은 특징을 가지고 있다. Correa-Rodríguez et al. [26]의 선행연구에 의하면 마른 비만을 가진 젊은 성인은 정상 BMI 및 체지방률을 가진 젊은 성인에 비해 절대 악력(handgrip strength)과 악력을 제지방량(handgrip strength to fat free mass ratio) 또는 체질량(handgrip strength to body mass ratio)으로 보정한 상대 악력 모두 낮았으며, 다른 선행연구에서는 마른 비만 집단은 정상 BMI와 체지방률을 가진 집단에 비해 골격근육량이 낮은 특징을 가진 것으로 보고되었다[11,12,24,45]. 인체에 약 30-40%를 차지하는 조직인 골격근은 glucose transporter type 4 전위(translocation)를 통해 글루코스(glucose)의 세포내 흡수에 중요한 역할을 하는 조직이며[48,49], 지방 산화(fat oxidation)와 전신 단백질 함량 및 신진대사(systemic metabolism)에 중추적인 역할을 하는 조직이다[50,51]. 이러한 골격근의 역할로 인해 골격근육량은 인슐린 저항성 및 지질 성분(lipid component)과 관련이 있는 것으로 알려져 있다[52,53]. Madeira et al. [36]의 연구에 의하면 정상 BMI 및 체지방률을 가진 젊은 성인보다 마른 비만을 가진 젊은 성인은 공복혈당(fasting glucose, FG), LDL-C, TG 및 인슐린 저항성이 높고, HDL-C 및 인슐린 민감성은 낮은 특징을 가지고 있다. 다시 말해, 마른 비만과 같이 골격근육량이 적을 경우 글루코스 대사 및 지질 대사에 부정적인 영향을 미치게 되어 인슐린 저항성 및 이상지질혈증과 같은 대사 질환의 위험성에 노출될 수 있다[34,52,53].

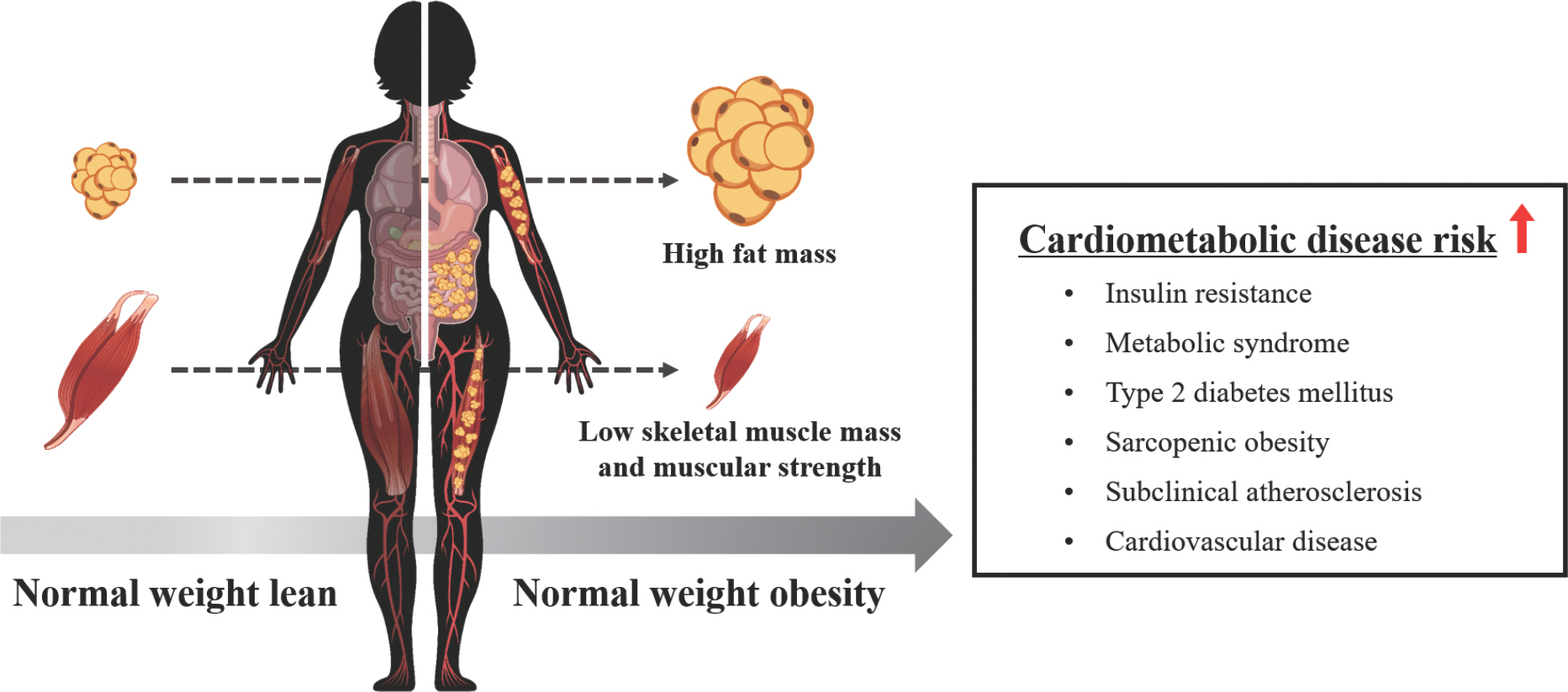

추가적으로 약 7년에 걸친 한 종단연구에서는 마른 비만을 가진 여자 어린이 및 청소년은 대사 및 심혈관계 질환 위험성에 노출되어 이로 인해 성인기에 질환 이환율이 증가할 수 있음을 제시하였다[27]. 또한 약 9년에 걸친 한 종단연구에서는 마른 비만이 있는 성인은 정상 범위의 BMI 및 체지방률을 가진 성인들에 비해 대사증후군 발병률이 약 4배 더 높은 것으로 나타났고, 특히 마른 비만 여성은 심혈관계 질환으로 인한 사망률이 약 2.2배까지 증가할 수 있어 심혈관계 사망 증가와 독립적으로 관련된 것으로 보고되었다[45]. BMI와 체지방률이 정상인 그룹(normal weight lean)과 비교한 마른 비만의 대사 및 심혈관계 질환 위험성과 관련된 선행연구를 종합한 내용은 Fig. 1과 Table 1에 요약하여 제시하였다[11,12,20,24,26,36,37,42,45,54,55].

종합해보면, 마른 비만은 신체적 특징으로 인하여 대사 및 심혈관계 질환 위험성에 노출되어 있으며, 이를 극복하기 위해서 선제적으로 마른 비만자를 선별하고 중재를 통한 질환의 위험성을 적극적으로 예방 및 개선할 필요성이 있다. 또한 마른 비만의 특성에 관한 선행연구들을 분석한 결과 BMI 단독으로는 대사 및 심혈관 질환을 예측하는 데 한계가 존재할 수 있으며, BMI와 함께 근육량 및 체지방률 등의 신체조성을 같이 파악하는 것이 잠재적인 대사 및 심혈관 질환을 예측할 때 유용할 것이라 판단된다.

2. 마른 비만 개선을 위한 저항성 운동의 잠재적 효과

마른 비만의 질환 위험성 예방 및 개선을 위해서는 체지방 감소와 근육량 증가 등 전반적인 신체조성의 변화를 유도할 수 있는 운동 중재가 필요하다. 운동 유형 중 저항성 운동(resistance exercise)은 인슐린 유사 성장인자(insulin-like growth factor-1, IGF-1) 분비를 유도하여 phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of ra-pamycin (PI3K/AKt/mTOR) 신호전달 기전을 활성화시켜 근육 단백질 합성을 촉진한다[56–58]. 또한, 최근 Pérez-López et al. [59]의 연구에 의하면 저항성 운동은 골격근에서 발현되는 마이오카인(myokine)으로 알려진 IL-15과 IL-15 receptor α의 발현을 통해 마이오신 중쇄 사슬(myosin heavy chain)의 축적을 유도할 수 있으며, 이를 통해 근원섬유 단백질(myofibrillar protein) 합성을 증가시킬 수 있는 것으로 보고되었다. 저항성 운동으로 인한 골격근육량의 증가는 기초대사율을 높여 체지방을 감소시킬 수 있기 때문에, 저항성 운동은 비만과 관련된 위험요인을 감소시키는데 효과적인 운동이다[60,61]. 미국심장협회(American Heart Association)와 미국스포츠의학회(American College of Sports Medicine, ACSM)에서는 건강증진 및 심혈관계 기능 향상을 위해서 주요 근육군을 포함한 8-10가지 다른 운동을 한 세트당 8-12회 반복하는 저항성 운동을 권고하고 있다[62,63]. Kelly et al. [64]의 메타분석 결과에 의하면 최소 4주 이상 규칙적인 저항성 운동에 참여하는 것은 TG, 총콜레스테롤(total cholesterol, TC), LDL-C, TC/HDL-C을 감소시키는 등의 대사 및 심혈관계 질환 위험성을 개선시키는 이점을 제공한다고 보고하고 있다.

남성보다는 여성에게서 빈번하게 나타나는 마른 비만의 경우, 일반적인 체중 감량보다는 저항성 운동을 통해 근육량 증가와 함께 체지방 감소를 유도하는 것이 효과적이라고 제시되고 있다[16]. Kim et al. [16]의 연구에 의하면 5주간의 중강도 저항성 운동은 젊은 마른 비만 여성의 근육량과 무산소성 파워 및 HDL-C을 증가시키는 것으로 보고되었다. 또한 Ferreira et al. [65]의 연구에 의하면 10주간의 서킷 저항성 운동은 마른 비만 여성의 체지방률 및 FG를 감소시킬 수 있고, 골격근육량은 증가시킬 수 있는 것으로 보고되었다. 뿐만 아니라, 서킷 저항성 운동을 통해서 연구 대상자의 약 30%는 10주간의 중재 후에 체지방률이 30% 미만으로 감소되어 마른 비만이 효과적으로 개선된 것으로 나타났다[65]. 따라서 저항성 운동 중재는 마른 비만의 대사 및 심혈관 건강을 개선하는 데 유용한 전략으로 제안될 수 있다.

하지만, 저항성 운동 시 고강도로 진행할 경우 숙련되지 않은 초보자에게는 부상의 위험성이 존재한다. 마른 비만과 같은 근력과 근육량이 낮은 대상자들에게는 저항성 운동 시 안정성과 운동 지속 동기를 높이기 위해서 고강도 저항성 운동 보다는 저강도 또는 중강도 저항성 운동이 효과적일 수 있다. 마른 비만자에게 저항성 운동이 적합한 운동 방법일 수 있지만, 선행연구들이 제한적이므로 향후 적절한 저항성 운동법 및 강도 적용에 대한 연구들이 필요하다.

3. 마른 비만 개선을 위한 혈류제한 저항성 운동의 잠재적 효과

저항성 운동의 효율성을 높이는 방법은 운동 양(volume), 부하(load), 휴식 시간, 반복 속도, 빈도 등 운동 프로그램의 변수들을 조작(manipulation)하는 것이다[66]. 저항성 운동의 효율성을 높이기 위한 또 다른 조작 전략에는 운동 중 근육 내 국소적인 저산소(hypoxia) 환경을 유발할 수 있는 혈류제한 저항성 운동(blood flow restriction resistance exercise)이 있다[67]. 혈류제한 저항성 운동은 사지 근위 부분에 압력 센서가 있는 탄성 재질의 커프를 착용하여 혈류를 제한하고 실시하는 저항성 운동 방법이다. 압력 커프로 인해 사지로 순환하는 혈류가 제한되고, 이로 인해 정맥 회귀(venous return)가 감소되어 근육 내 저산소 환경 및 대사 산물의 축적을 유발한다[67,68]. 특히, 저강도 혈류제한 저항성 운동은 일반적인 중 ∙고강도 저항성 운동과 유사한 정도로 성장호르몬(growth hormone, GH), IGF-1, 젖산(lactic acid) 등의 증가를 유도하여 저강도 운동으로도 긍정적인 생리적 효과를 나타낼 수 있다고 알려져 있다[68–70]. 또한 Karabulut et al. [71]의 연구에 의하면 1RM 20%의 저강도 혈류제한 저항성 운동이 1RM 80%의 일반적인 고강도 저항성 운동과 유사한 근력 향상 효과를 볼 수 있다고 보고하였다. 그뿐만 아니라, 한 메타분석 결과에 의하면 저강도 혈류제한 저항성 운동은 노인의 근력 및 근육량을 증가시킬 수 있는 것으로 보고되었으며, 노인과 같은 체력 수준이 낮은 대상자들에게도 효과적인 중재 방법임이 제시되었다[72]. 즉, 혈류제한 저항성 운동은 호르몬 변화와 같은 생리적 반응을 효율적으로 자극하여 여성, 노인, 재활환자 등과 같은 중 ∙고강도 저항성 운동을 실시하기 어려운 대상자들에게 부상의 위험을 낮추면서, 저강도 운동으로도 근력 향상 및 근비대 효과를 나타낼 수 있는 이점이 있다[16,67,68,71-73].

또한 혈류제한 저항성 운동은 심혈관 기능 향상에 긍정적인 영향을 끼친다. Ferguson et al. [74]의 연구에 의하면, 1회성 저강도 혈류제한 저항성 운동은 건강한 젊은 성인 남성의 내피 산화질소 합성효소(endothelial nitric oxide synthase, eNOS), 혈관내피성장인자(vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF), VEGF receptor 2, 저산소증 유도 인자 1α (hypoxia-inducible factor 1α)의 mRNA 발현을 증가시켰다. 이로 인해 저강도 혈류제한 저항성 운동은 허혈(ischemia) 및 전단 응력(shear stress)을 향상시켜 혈관신생(angiogenesis) 반응을 유도할 수 있다고 제시되었다[74]. 또한 다른 선행연구는 4주간의 저강도 혈류제한 저항성 운동을 통해 노인의 혈관내피세포 기능 및 말초 혈액 순환을 개선시키는 결과를 보여주었다[75]. 또 다른 메타분석 결과도 저강도 혈류제한 저항성 운동은 혈관내피세포 기능을 향상 시킬 수 있다고 보고하였다[76]. 따라서 저강도 혈류제한 저항성 운동은 혈관 기능 향상을 유도할 수 있는 효과적인 운동 중재 방법으로 제안될 수 있다.

마른 비만과 같은 근육량이 적고 체지방률이 높은 대상자들에게도 혈류제한 저항성 운동은 근력 향상 및 근육량의 증가를 유도하는 효율적인 방법으로 제시될 수 있다. 실제로 Kim et al. [16]의 연구에 의하면 5주간 1RM 40%의 비교적 낮은 강도의 혈류제한 저항성 운동은 체력 수준이 낮은 젊은 마른 비만 여성의 근력 및 무산소성 파워를 향상 시키는 결과를 보여주었다. 하지만, 일반적인 중강도 저항성 운동과는 달리 근육량의 증가와 혈중 지질의 개선을 보여주지는 못하였다[16]. 마른 비만을 대상으로 혈류제한 저항성 운동을 중재한 연구는 제한적이므로, 그 효과를 검증하기에는 한계가 존재한다. 하지만, 많은 선행연구에서는 혈류제한 저항성 운동 시 내분비계, 대사계, 심혈관계 등의 활성이 자극되고, 이로 인해 저강도의 부하에서도 근력 및 근육량의 증가와 함께 대사 및 심혈관 기능의 향상이 유도될 수 있다고 보고되고 있다[69,70,75-79]. 이러한 점을 고려했을 때, 혈류제한 저항성 운동은 마른 비만을 대상으로도 호르몬 변화 및 신체조성의 개선과 같은 긍정적인 효과가 나타날 수 있으며, 이는 마른 비만에게 적합한 운동 중재 방법이 될 가능성이 존재한다.

저강도 혈류제한 저항성 운동은 일반적인 중 ∙고강도 저항성과 유사하게 생리적 반응을 자극하여 근육량 증가 효과를 나타낼 수 있으면서, 일반적인 중 ∙고강도 저항성 운동 보다 안정성과 운동 지속 동기를 높일 수 있을 것이라 판단되지만, 일부 고려할 사항이 존재한다. 혈류제한 저항성 운동 시 사지의 혈류를 제한하기 위한 커프에 가해지는 압력이 강해질수록 운동량이 감소하고 불편함을 느낄 수 있다[80]. 따라서 혈류제한 저항성 운동 시 개인의 수축기 혈압(systolic pressure) 또는 동맥 폐쇄 압력(arterial occlusion pressure)을 고려하여 혈류제한을 위한 압력 강도를 설정할 필요가 있으며, 안전하고 적절한 압력 강도 설정에 관한 연구가 더욱 필요한 실정이다[16,81,82].

4. 마른 비만 개선을 위한 고강도 인터벌 운동의 잠재적 효과

운동 유형 중 고강도 인터벌 운동(high intensity interval exercise)은 고강도 운동 구간 사이에 휴식 또는 저∙중강도 운동이 반복된 운동의 형태이다. ACSM 피트니스 트렌드에 의하면 고강도 인터벌 운동은 2014년부터 2020년까지 트렌드 한 운동 중 상위 5위 안에 들면서 전 세계적으로 지속적인 인기를 얻고 있다[83]. 고강도 인터벌 운동은 인기와 더불어 체지방 감소 및 골격근 대사 조절을 통해 다양한 생리적 적응을 유발하여 건강상의 이점을 제공하는 것으로 알려져 있다[84]. Gibala et al. [85]의 연구에 의하면 1회성 고강도 인터벌 운동 직후 젊은 성인 남성의 골격근에서 adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK)와 p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) 신호전달이 활성화되고, 운동 후 3시간 뒤에는 미토콘드리아 생물발생(biogenesis)의 ‘ master regulator’로 알려진 peroxisome proliferator-acti-vated receptor gamma coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) mRNA 발현이 증가된다는 결과를 보고하였다. 또한 Burgomaster et al. [86]의 연구에 의하면 건강한 젊은 성인을 대상으로 6주간의 무산소성 윈게이트 검사(Wingate Test)를 활용한 고강도 인터벌 운동 중재는 중강도 지속성 운동과 비교했을 때, 운동량은 약 1/10 (~225 KJ vs. ~2,250 KJ week−1), 운동 시간은 약 1/3 (~1.5 hours vs. ~4.5 hours week−1) 정도로 낮았음에도 불구하고, 골격근에서의 PGC-1α 단백질 발현 및 산화 능력은 유사하게 증가시켰다. 골격근에서 PGC-1α의 증가는 산화 능력 증가, 인슐린 민감성 개선, 근감소증에 대한 저항 등 다양한 긍정적인 효과를 유도한다는 점을 고려했을 때[87,88], 고강도 인터벌 운동 후 PGC-1α의 증가는 골격근 대사 조절을 통해 광범위한 건강상의 이점을 제공할 수 있을 것이다[84]. 추가적으로 최근 Marcangeli et al. [89]의 연구에 의하면, 비만 노인을 대상으로 12주간 고강도 인터벌 운동은 근육량 증가 및 체지방률 감소 등 신체조성 개선과 함께 미토파지(mitophagy), 미토콘드리아 결합(fusion) 및 미토콘드리아 생물발생을 향상시키는 결과를 보여주었다. 이러한 결과는 고강도 인터벌 운동이 신체조성의 변화 및 미토콘드리아 기능 향상을 통해 비만 개선에 안전하고 효과적인 운동임을 제시할 수 있다[89].

또한 고강도 인터벌 운동은 중강도 지속성 운동과 비교해 볼 때, 적은 운동 시간에 비해 비슷하거나 더 뛰어난 심폐지구력 향상을 유도할 뿐만 아니라, 혈관내피세포 기능 향상 및 동맥경직도 감소 등 심혈관 기능 개선에 이점을 제공할 수 있는 것으로 알려져 있다[90–94]. 결과적으로 고강도 인터벌 운동은 대사 및 심혈관 위험인자를 개선할 뿐만 아니라, 시간 효율적(time-efficient)인 장점을 가지고 있기 때문에, 일반적으로 신체활동의 장벽으로써 언급되는 “시간 부족(lack of time)”을 완화할 수 있다[95,96]. 따라서 고강도 인터벌 운동은 현대인의 바쁜 일상 속에서 짧은 운동 시간으로 장시간 운동만큼 효과를 나타낼 수 있는 점에서 매력적인 운동 중재 방법으로 제시될 수 있다.

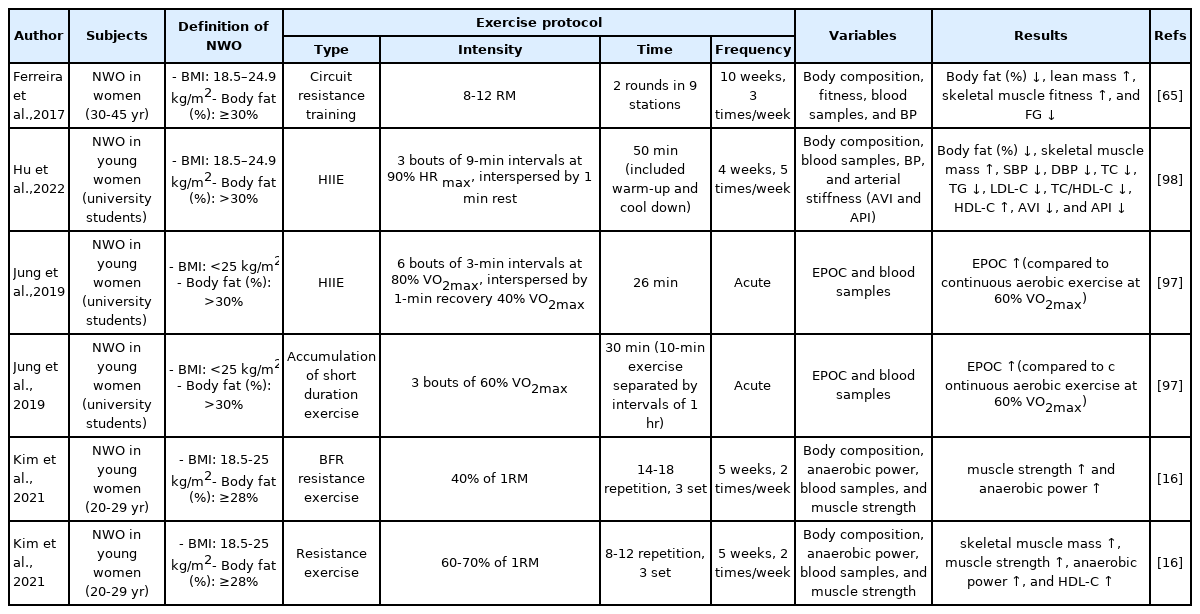

시간 효율적이고, 체력 향상 및 체지방 감소를 유도하는 측면에서 볼 때, 고강도 인터벌 운동은 마른 비만인에게도 적용 가능한 운동 중재 방법이다. Jung et al. [97]의 연구에 의하면 젊은 마른 비만 여성을 대상으로 1회성 고강도 인터벌 운동은 중강도 지속성 운동에 비해 운동 후 초과 산소섭취량(excess post-exercise oxygen consumption)을 증가시켰다. 이를 통해 고강도 인터벌 운동은 마른 비만 여성의 에너지 소비를 효과적으로 증가시킬 수 있는 운동 중재 방법으로 제시되었다[97]. Hu et al. [98]의 연구에 의하면 4주간의 고강도 인터벌 운동은 젊은 마른 비만 여성의 체지방률을 감소시켰고, 골격근육량을 증가시켰다. 그뿐만 아니라, TC, TG, LDL-C, TC/HDL-C 감소와 HDL-C의 증가를 나타냈으며, 이러한 결과들을 통해 고강도 인터벌 운동은 마른 비만 여성의 신체조성의 개선과 함께 대사 및 심혈관 질환의 위험성을 개선할 수 있다는 결과를 보고하였다[98]. 또한 여러 메타분석 결과들에 의하면, 고강도 인터벌 운동은 건강한 성인뿐만 아니라, 과체중, 비만, 제2형 당뇨병 등 대사 질환을 가진 대상자들의 체력 향상과 대사 및 심혈관 위험인자의 개선을 유도하는 것으로 나타났다[99–101]. 이러한 점을 고려했을 때, 대사 및 심혈관 질환의 잠재적인 위험성을 가진 마른 비만인에게도 고강도 인터벌 운동은 효과적인 운동 중재 방법으로 제시될 수 있을 것이다. 운동 중재에 따른 마른 비만의 신체조성과 대사 및 심혈관계 위험인자에 미치는 영향에 대한 선행연구를 종합한 내용은 Table 2에 요약하여 제시하였다.

결 론

본 종설에서는 BMI가 정상 범위에 속하지만, 근육량은 적고 체지방률이 비만에 해당되는 새로운 비만의 범주인 마른 비만에 대한 대사 및 심혈관 질환 위험성에 관한 선행연구들을 분석하여 마른 비만의 질환 위험성을 선제적으로 예방하기 위한 운동 중재 방법을 고찰한 결과 다음과 같이 요약∙정리할 수 있다.

마른 비만은 전 세계적으로 남성보다는 여성에게서 더 많이 나타나며, 어린이, 청소년, 젊은 성인 및 중 ∙노년 등 전 연령층에서 빈번하게 나타난다. 마른 비만은 체중 대비 과도한 체지방과 적은 근육량이라는 신체적 특성으로 인하여 내장지방, 중성지방, 이소성 지방량이 많고, 산화 스트레스, 염증성 사이토카인, 공복혈당 및 인슐린 저항성이 높다[17,21,36]. 또한 마른 비만은 HDL-C이 낮고, LDL-C, 혈압, 동맥경직도 및 관상동맥 내 연성 플라크(soft plaques)가 높아 무증상 죽상동맥경화증의 가능성이 있어 잠재적으로 관상동맥질환의 높은 발병 위험성이 있는 것으로 보고되었다[42]. 약 9년에 걸친 종단적 연구에 의하면, 마른 비만자는 대사 및 심혈관계 질환 이환율 및 사망률이 증가되는 결과를 보여주었다[45]. 따라서 마른 비만은 병태생리학적 변화로 인한 대사 및 심혈관계 질환 위험성이 존재하므로, 이를 극복하기 위해서 마른 비만자를 적극적으로 선별하여 운동 중재를 통한 질환의 위험성을 선제적으로 예방 및 개선할 필요성이 있다.

마른 비만의 질환 위험성을 선제적으로 예방하기 위해서는 체지방 감소와 근육량 증가가 동시에 이루어질 수 있는 운동 중재가 필요하다. 마른 비만을 대상으로 신체조성의 변화를 유도할 수 있는 운동 중재 방법으로 저항성 운동, 혈류제한 저항성 운동, 고강도 인터벌 운동 등을 제시할 수 있다. 먼저 저항성 운동은 마른 비만 여성의 근육량 및 무산소성 파워를 증가시킬 수 있고, 혈중지질 개선을 유도할 수 있다[16]. 또한 10주간의 서킷 저항성 운동은 마른 비만 여성의 근육량을 증가시키고, 체지방률을 감소시킴으로써 마른 비만자에게 효과적인 운동 중재임을 제시하였다[65]. 또 다른 운동 유형 중 혈류제한 저항성 운동은 상대적으로 저강도로도 마른 비만 여성의 근력 및 무산소성 파워를 향상시키는 결과를 보여주었다[16]. 혈류제한 저항성 운동은 마른 비만과 같은 근력이 낮고 근육량이 적은 대상자들에게 저강도로도 일반적인 중 ∙고강도 저항성 운동과 유사하게 호르몬 변화와 같은 생리적 반응을 자극하여 근력 향상 및 근육량 증가를 유도할 수 있어 매력적인 운동이 될 수 있지만, 연구가 매우 제한적이므로 마른 비만을 대상으로 효과를 검증하기에는 한계가 존재한다. 마지막으로 고강도 인터벌 운동은 마른 비만 여성의 골격근육량 증가 및 체지방률 감소 등 신체조성의 변화를 유도할 뿐만 아니라, 혈압과 동맥경직도를 감소시키고, 혈중 지질을 개선시켰다[98]. 이로 인해 고강도 인터벌 운동은 마른 비만 여성의 신체조성의 개선과 함께 대사 및 심혈관 질환의 위험성을 감소시킬 수 있는 운동으로 제안될 수 있다.

현재까지 진행된 마른 비만에 관한 연구는 마른 비만의 질환 위험성을 제시하는 연구가 집중적으로 이루어져 왔다. 마른 비만은 대사 및 심혈관 질환 이환율과 사망률에 밀접한 관련이 있으나, 마른 비만의 질환 위험성 예방을 위한 효과적인 운동 중재에 관한 연구는 아직까지 미미한 실정이다. 이에 본 종설은 마른 비만의 대사 및 심혈관 질환 위험성 예방의 관점에서 다양한 운동 중재의 효과를 설명하였으며, 마른 비만자를 위한 효과적인 운동 방법으로 저항성 운동, 혈류제한 저항성 운동, 고강도 인터벌 운동을 제시하고자 한다. 이는 마른 비만을 위한 효과적인 운동 중재 발굴에 시사점을 줄 수 있고, 향후 마른 비만에 예방적 차원의 운동 중재에 대한 심도 깊은 연구의 필요성을 제시할 수 있다.

Notes

이 논문 작성에 있어서 어떠한 조직으로부터 재정을 포함한 일체의 지원을 받지 않았으며, 논문에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 어떠한 관계도 없음을 밝힌다.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: M Ji, C Cho, S Lee; Data curation: M Ji; Formal analysis: M Ji; Funding acquistion: S Lee; Methodology: M Ji, C Cho; Vi-sualization: M Ji; Writing - original draft: M Ji, C Cho; Writing - review & editing: S Lee.