Korean Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool 6th Edition (SCAT6): Reliability and Validity

Article information

Abstract

PURPOSE

This study aimed to establish a contemporary, standardized Korean version of the Sports Concussion Assessment Tool 6th edition, characterized by superior face validity and reliability.

METHODS

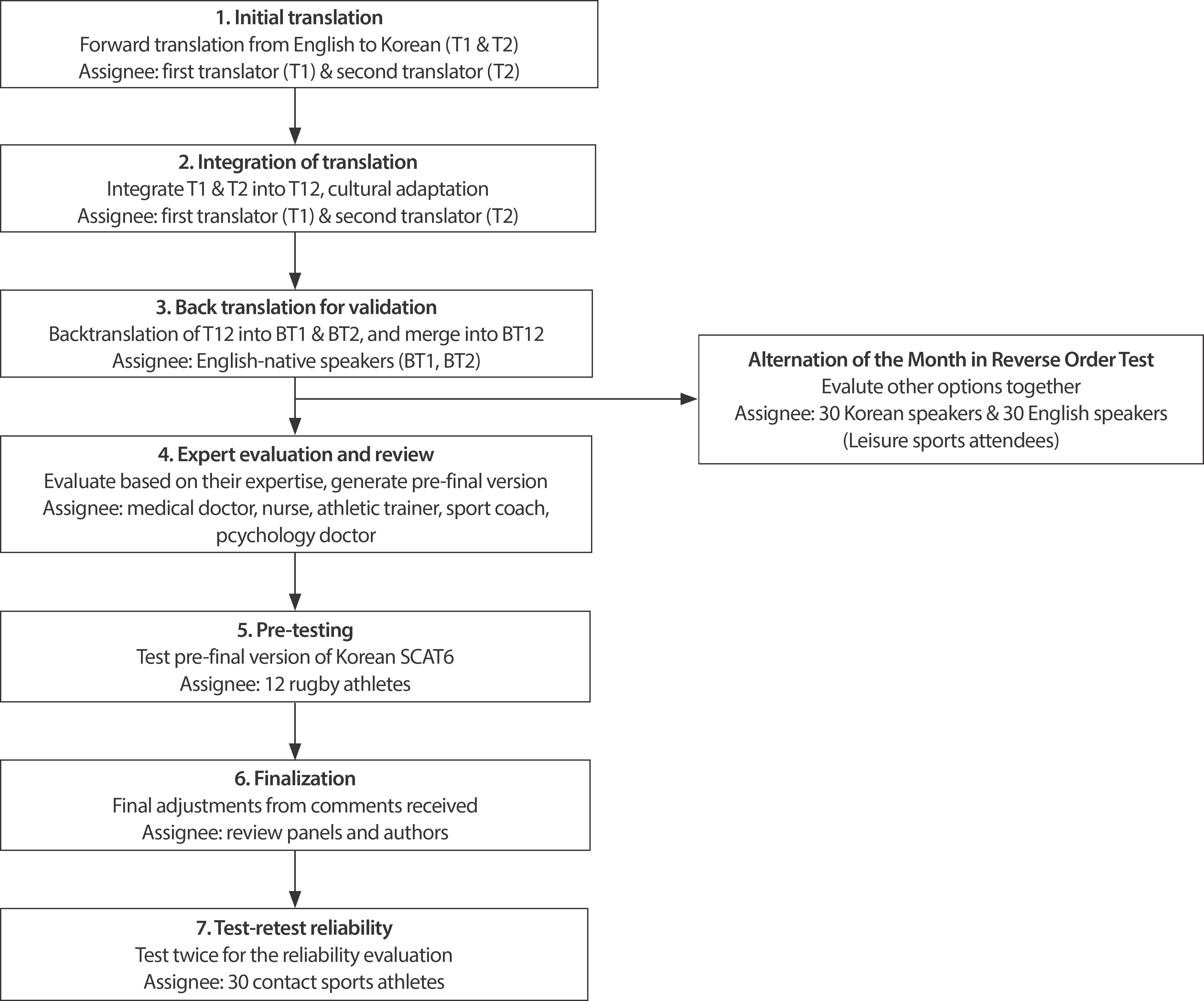

Translation and cultural adaptation involved seven stages, namely initial translation, integration of translation, back translation, validation with five expert committees, pre-testing with 12 rugby athletes, finalization, and a test-retest with 30 rugby and American-football athletes. Alternative tests were conducted for the Months In Reverse Order Test due to the naming differences between English and Korean.

RESULTS

The English Months In Reverse Order Test took 11.00±2.69 seconds with a difficulty of 2.27±0.98 points, while the Korean Months In Reverse Order Test took 5.69±1.35 seconds with a difficulty of 1.50±0.73 points (p<.001). The Adding Serial 3s Test and Days of the Week Backward Test were evaluated for completion time, difficulty, and accuracy in 30 English and 30 Korean participants. The results of the Korean Adding Serial 3s Test were poor (time 10.50±3.55 seconds; difficulty 2.97±1.25 points), while The Korean Days of the Week Backward Test was fast and easily replaced Months In Reverse Order Test (time 3.46±0.72 seconds; difficulty 1.5±0.82 points). An attempt with Korean Months In Reverse Order Test and Days of the Week Backward Test, where participants were asked to recite all at once, yielded acceptable results (time 10.62±2.04 seconds; difficulty 1.90±0.99 points) compared to English Months In Reverse Order Test (p>.05). The face validity was adequate and reliability was mostly high (Cronbach alpha=0.79).

CONCLUSIONS

The results indicate that The Korean Sports Concussion Assessment Tool 6th edition was well translated and exhibited adequate face validity and reliability.

INTRODUCTION

Sports-related concussions (SRC) are traumatic brain injuries characterized by complex pathophysiological processes within the brain. They result from biomechanical forces and share common features that define their nature [1]. According to the Centers for Disease Control, from 2001 to 2009, the estimated number of visits to hospital emergency departments for SRC increased by 62% in persons 19 years or younger [2]. The increasing frequency of SRC and the emerging possible long-term health risks continue to raise concerns in the healthcare community, the gener-al public, and those who set public policy [3]. However, the current definition and diagnostic criteria for SRC are clinically oriented, and a universally recognized gold standard for assessing their diagnostic properties is lacking [1].

To diagnose concussions comprehensively, a multimodal evaluation encompassing athlete symptom reports, neurological signs, cognitive status, balance and gait assessments, and oculomotor/vestibular evaluations is required [4]. The Sport Concussion Assessment Tool (SCAT), developed by the Concussion in Sports Group (CiSG), is a widely recognized standardized assessment tool that incorporates these elements, primarily designed for sports-related evaluations [5]. SCAT6 has the ad-vantage of being developed specifically for use in sports and is designed to standardize acute clinical evaluation.

South Korea, a sports powerhouse, conversely lacks comprehensive data on SRC [6,7]. In a previous study, no athletes correctly identified all signs and symptoms, and approximately 63.9% of athletes who reported SRC made return-to-play decisions [7]. These results reflect the lack of knowledge among South Korean athletes.

Nevertheless, SCAT6 was developed in English, and SCAT3 and SCAT5 have been widely used in English-speaking countries, necessitating translation to ensure its global applicability [8-10]. Moreover, English proficiency among Korean athletes is limited [11], making it imperative to provide concussion assessment tools in their native language.

Furthermore, certain components of the SCAT may not be suitable for the Korean culture and language. Similar challenges were encountered during the translation of SCAT into Arabic and Chinese, necessitating the replacement of specific tests like “ Months In Reverse Order Test (MIROT)” with culturally appropriate alternatives [8,11]. Therefore, there is evident need for culturally adapted concussion assessment tools in Korea.

SCATs must be culturally adapted to be used globally. Therefore, in countries where English is not commonly used, efforts have been made to translate and adapt the tools for use in their native languages [8,9,12]. To date, the concussion evaluation tools used in Korea are limited and no other translated SCAT has checked for both validity and reliability. To enhance the recognition, reporting, evaluation, and management of sports concussions, we aim to make concussion assessment tools more accessible to sports and medical experts, as well as athletes whose preferred language is Korean. Therefore, this study aimed to translate the SCAT6, which is currently available in English [5], into the modern Korean standard and culturally adapt it accordingly.

METHODS

1. Participants

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University (IRB No. 2308/002-018). Written approval was obtained from CiSG. During the visit, the purpose and content of the study were explained to the participants in an explanatory document, and their agreement was obtained through written consent forms.

A previous study [8] that translated the SCAT5 into Arabic laid the groundwork for this study. In this study, to replace the “ MIROT” we included 30 English and 30 Korean speakers who are engaging in recre-ational sports for the “ alternative test” and 12 rugby athletes for the “ pre-testing” phase. Additionally, for the “ test-retest reliability examination”, 30 contact sports athletes were recruited (29 rugby and 1 American football). In total, 102 participants who had never previously undergone SCAT were included in this study. The basic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

2. Research execution process

Translation, adaptation, and validation were conducted in 7 steps ac-cording to Fig. 1 [8,13].

The stages of Korean cross-cultural translation and adaptation of the sport concussion assessment tool 6th edition.

Step 1: Initial translation.

The initial translation was conducted by two native Koreans proficient in English and Korean. One was an experienced translator with prior knowledge of SCAT6 (T1), whereas the other was a qualified translator who was not acquainted with SCAT6 (T2). They independently translated the SCAT6 into Korean, with a focus on ensuring cross-cultural equivalence and applicability.

Step 2: Integration of translations.

The two translators combined the initial translations of the Korean SCAT6 to create a single translation (T12), produced by the first translator (T1), and second translator (T2). They meticulously documented the integration process, addressed any issues encountered, and outlined the techniques used in written reports. This step aimed to provide a cultural adaptation that could be comprehended by medical professionals and athletes whose native language is Korean. In line with previous research, each sentence in the Korean SCAT6 translation was examined for semantic, idiomatic, experiential, and conceptual equivalence.

Step 3: Back-translation.

The T12 version was independently back-translated into English by two back-translators (BT1 and BT2), one based on sports science (BT1), and both native English speakers with no prior knowledge of the SCAT6. This was performed to validate whether the Korean translation accurately conveyed the content and meaning of the original text. The same process applied to T12 was used to merge the two back-translated texts (BT1 and BT2) into a single back-translation (BT12).

Step 4: Expert Evaluation & review.

The review panel consisted of medical doctors, nurses, rugby coaches, athletic trainers, and sports psychology specialists. Their role was to comprehensively evaluate and harmonize the discrepancies among the various versions of the tools (T1, T2, T12, BT1, BT2, and BT12) based on their respective areas of expertise. They collectively examined all the translated documents, especially the unmatched parts, and reached a consensus on any inconsistencies, considering factors such as semantic, idiomatic, experiential, and conceptual equivalence, all of which were documented in a written report. After adjusting for their report, they were instructed to rate the similarity and comparability of the pre-final version on a 7-point Likert scale, where 1=very similar/comparable and 7=entirely dissimilar/incomparable. Then, the results of the similarity and comparability were reviewed again when they were above 2.5, and the necessary adjustments were made to generate the final version of the Korean SCAT6 for use in the pre-test.

Step 5: Pre-testing before finalization.

The pre-final version of the Korean SCAT6 was tested on 12 Korean native rugby athletes by one of the researchers, and their feedback regarding the clarity, comprehensibility, lack of confusion, and consistency of the test was collected in a report form.

Step 6: Finalization.

Considering all the comments received during the pre-test, some adjustments were made and the final version of the Korean SCAT6 was developed.

Step 7: Test-retest reliability.

A total of 30 contact sports athletes participated in two tests within a single day. To mitigate the effects of adaptation/learning, a 30-minute cycling session and a numeric quiz were administered between the trials. The time gap between the trials was approximately 50 minutes, with the same evaluator overseeing both. Each sentence was read aloud in the same manner, with no additional information provided. Since SCAT6 is not a test for correct answers but rather for attention, memory, and physical reaction, it offers 3 different options with the same phonetic pattern for Immediate Memory, Backward Digit Test, and Dual Task Gait to account for potential adaptation effects (See Original SCAT6 or Appendix 1). We therefore used different options for the test-retest reliability examination.

3. Alternative to the Months In Reverse Order Test

During the Korean SCAT6 translation, concerns about the MIROT arose because Korean months are numeric. Chinese and Arabic translations face similar challenges which month in English is more complicat-ed (e.g., January, February, etc.) than in numeric (Month 1, Month 2, etc.). Alternative assessments, such as the Days of the Week Backward Test (DWBT) and the Adding Serial 3s Test, were considered based on similarities with previous studies. These studies adopted DWBT and Addition of Serial 3s as alternatives to MIROT, given their utilization of numerical terms similar to those used in referring to “ Month.”

The MIROT involves verbally listing months backward in less than 30s, scoring one point for completion within the time limit [12,14]. The DWBT reverses the days of the week, and Adding Serial 3s counts from 1 to 40 in threes for example, 1, 4, 7, …, 40 [15,16]. To evaluate these alternatives, 30 English and 30 Korean speakers participating in recre-ational sports completed the MIROT, DWBT, and Adding Serial 3s in a randomized order with 1-minute intervals. The accuracy, completion time were recorded and perceived difficulty was recorded on 5-point Likert scale, with 1 representing “ very easy” and 5 representing “ very difficult.”

The results showed that both tests were unsuitable substitutes for the MIROT (explained in the “ Results”). Consequently, the MIROT and DWBT were integrated into a single test. Ten additional Korean participants completed the test, consecutively reversing months and days. The completion time and difficulty were recorded.

4. Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were reported as means and standard deviations. An independent t-test was employed to compare the difficulty of rating and the time taken for tasks such as the MIROT, DWBT, and Adding Serial 3s Tests between English and Korean speakers. To evaluate the reliability within a day, the results from two individual trials were used for Cronbach's alpha (>0.9, excellent reliability; 0.7-0.9, high reliability; 0.5-0.7, moderate reliability; 0.5 and below, low reliability; and >0.7 was considered acceptable) and Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) (>0.9, excellent reliability; 0.75-0.9, good reliability; 0.5-0.75, moderate reliability; 0.5 and below, poor reliability) [17,18]. The significance level was set at p <.05.

RESULTS

1. Translation and adaptation

Several problems were identified in the initial Korean SCAT6 translation, such as inconsistent endings (In Korean, unlike in English, verbs are located at the end of sentences, and even one English verb can be translated into various ending tones), inaccurate translations of medical terms, and inappropriate literal translations without cultural adaptation, all of which were resolved. Specific changes were made to the Immediate Memory Test (Table 2).

2. Review

The review panels discussed each sentence in the initial Korean SCAT6 translation for semantic, idiomatic, experiential, and conceptual equivalence, until a consensus was reached. As an Immediate Memory Test sensitive to word length and phonological similarity [19], word lists were derived from sets of commonly used and phonologically similar English word [7]. Therefore, the substitution of English words in the Immediate Memory Test was based on the following three aspects: (1) belonging to the same semantic domain, (2) having the same number of syllables, and (3) showing phonological similarities. Eight words were changed from the original English to Korean (Table 2).

3. Alternative to the Months in Reverse Order Test

After comparing MIROT performances between 30 Korean and 30 English speakers, the English MIROT proved to be significantly more challenging and time-consuming (Table 3). Seeking alternatives, DWBT, and Adding Serial 3s were considered. The Korean Adding Serial 3s Test took 10.50±3.55 seconds, similar to the English MIROT (11.00±2.69 seconds). However, the higher difficulty score and overlap with the counting tests in the updated SCAT6 led to its exclusion. DWBT,s short completion time (3.46±0.72 seconds) and lower difficulty (1.50±0.82 points) made it unsuitable as a standalone alternative. With an unexpected finding from this study compared to the previous studies, we have integrated the MIROT and DWBT into single assessment approved by the CiSG. The results for the single assessment, as presented in Table 4, offer a viable alternative to the English MIROT, demonstrating promising outcomes.

Alternative to the English Month in Reverse Order Test with Korean days week backward test and adding serial 3s test

4. Pre-testing

Twelve rugby players were tested using the pre-final version of the Korean SCAT6. The testing duration for the pre-final version averaged 21.01±3.34 minutes. Most athletes reported a comfortable understanding of the instructions in the SCAT6, facilitating a smooth test progression under the guidance of the evaluator. However, specific comments were raised, such as four athletes expressing difficulty in understanding the “ tandem stance” due to the less common usage of the term “ heel-to-toe” in Korea. Another comment highlighted confusion in the “ MIROT,” particularly regarding whether to start with December or November. Consequently, we implemented minor modifications and subjected them to subsequent review. To address the ambiguity associated with “ Heel-to-toe,” we revised the instruction to “ place your heel on the floor and toes, then walk quickly in a straight line, avoiding a stance similar to standing still.” Additionally, for the “ MIROT,” we clarified the starting point by specifying “ until January,” referring to the 1st month in Korean (e.g., 1월).

5. Face validity

Continuous feasibility assessments were conducted during the translation review process and all discussions were recorded. Furthermore, similarity/comparability ratings (1-7 points: 1=perfectly similar and comparable) were all below 2 and adjustments based on pre-test feed-back were conducted to support face validity. Appendix 1 presents the final version of the Korean SCAT6.

6. Test-retest reliability

Through a test-retest examination, excellent reliability was found for each test factors using Cronbach's alpha and ICC shown in Table 5. The reliability of Cognitive screening was average 0.691, Coordination and balance examination was average 0.833, and Delayed recall was 0.775. For total, it was 0.764 which showed high reliability and considered acceptable. In ICC, Cognitive screening was average 0.691, Coordination and balance examination was average 0.810, and Delayed recall was 0.741. For total, it was 0.764 which showed high reliability and considered acceptable.

DISCUSSION

This study's main aim was to undertake the translation and cultural adaptation of the English SCAT6 into Modern Standard Korean characterized by superior face validity and reliability. This marks the first instance of the SCAT series becoming accessible to the Korean population through dedicated translation efforts. In a broader context, it is pertinent to mention that, to our knowledge, SCAT6 has not undergone cultural adaptation in multiple languages, with only the Chinese and Arabic versions of SCAT3 and SCAT5 being validated. Furthermore, this research stands as the sole study to assess reliability across these versions. Intriguingly, all iterations, including the Korean version, face a common challenge related to the “ Months in Reverse” task.

Conducting MIROT poses challenges in regions that rely on numerical representations rather than monthly names. Countries such as China and Arabic-speaking nations have assessed MIROT in English and native languages, revealing differences with English MIROT [7,8]. Similarly, we hypothesized differences in the Korean MIROT. Initial alternatives considered were “ Adding Serial 3s” and “ DWBT”, following the similarity of the monthly names with the previous studies. However, the findings showed variations compared with those.

The English MIROT averaged 11.00 seconds, which was slightly faster than the English-speaking Arabic athlete MIROT averaged 15.5 seconds. Conversely, the Korean MIROT averaged 5.69 seconds, suggesting that it may not be a suitable replacement. Korean DWBT was deemed too easy and short, completing in 3.46 seconds with a difficulty rating of 1.50 points, compared to English MIROT,s 11.00 seconds and a difficulty rating of 2.27 points.

Incorporating “ Adding Serial 3s” extended the test duration (10.50s), but the difficulty slightly increased (2.97 points). However, “ Adding Serial 3s” revealed significant differences between the English and Korean versions, especially within SCAT6,s mathematical tests [12]. Consequently, MIROT was not replaced with “ Adding Serial 3s.” Instead, 30 Korean speaking participants were retested using “ MIROT+DWBT” consecutively (e.g., 12월, 11월, …, 1월, 일요일, 토요일, …, 월요일). Results indicated that this combination was the most suitable option, with English MIROT averaging 11.00 seconds and a self-rated difficulty of 2.27 points, while Korean MIROT+DWBT averaged 10.62 seconds with a self-rated difficulty of 1.90 points (p>.05). Additionally, this result was confirmed by the CiSG.

For the Memory Test (comprising an Immediate Memory Test and Delayed Recall), our initial approach was to translate English words di-rectly into Korean. However, it soon became apparent that some Korean English phrases did not have direct linguistic equivalents. Consequently, we selected Korean words with similar meanings or themes, considering the intensity and pronunciation of the original English words. For instance, “ Monkey„ was replaced with “토끼 [tokki]„ (rabbit), as it better matched the strong phonetics of the English word. Similar modifications were made to other words.

Our primary objective was to ensure that SCAT6,s core purpose re-mained intact while making culturally appropriate translations that res-onate with Korean culture. It is essential to highlight that the English SCAT6 is estimated to take more than 10-15 minutes to complete. Similarly, the Chinese SCAT3 took approximately 10.6±1.1 minutes and the Arabic SCAT5 took more than 20 minutes [7,8]. In the case of Korean SCAT6, the pre-test took an average of 21.01±3.34 minutes. Although direct comparisons with previous studies may be challenging owing to version differences, it is evident that our Korean version of the SCAT6 exceeds the recommendation which was more than 10-15 minutes completion time [12].

The reliability of each major assessment component was generally high during test-retest examinations, with the exception of the Digit Backward Test. However, this particular test may not be influenced by translation, as indicated in Appendix 1, as it involves recalling numbers in reverse order. Hence, the fluctuations observed may arise from individual variances in mathematical proficiency or memory among the athletes. Additionally, the limited scoring range might have influenced the results, as evidenced by similar means for each trial: 3.13±0.96 and 3.29±1.01 out of a total of 4.

Moreover, a study by Hänninen et al. investigated the reliability of the original version of SCAT5 and similarly found fluctuations in test-retest results, suggesting significant variability attributed to individual differences among athletes [20]. Despite this, our study primarily focused on translation and subsequent reliability and validity assessments, with no specific recommendations provided for addressing this issue.

The variability observed in the Digit Backward Test may also be influenced by the use of different options for repeated measurements, leading to variations based on participants, familiarity with the numbers used. Additionally, this discrepancy is likely unrelated to the translation process, given the straightforward nature of the test involving number recitation in reverse order. It appears to be an inherent challenge associated with conducting repeated measurements with different options to mitigate learning effects and adhere to the intended purpose of SCAT6 administration.

Nevertheless, previous studies have demonstrated discrepancies even when administering the same test repeatedly [20]. Therefore, future research should consider conducting reliability testing with longer intervals between assessments and a more diverse range of participants across all options to address the limitations associated with reliability assessment.

Overall, the introduction of the Korean version of the SCAT6 marks a significant advancement in the field of sports concussion assessment. This version has not been previously published with other language, and its introduction is expected to usher in a new era of sports concussion management in the Korean-speaking population. Moreover, cultural adaptation of cognitive testing was meticulously conducted, adhering to established guidelines for translation and cultural adaptation. This approach ensures semantic, idiomatic, experiential, and conceptual equivalence. It considers various linguistic factors, such as semantic domain, syllable count, and phonological qualities, thereby addressing the potential impact of these factors on the difficulty and usability of Immediate and Delayed Recall Test. This successful translation paves the way for efficient adaptation of the other 6th editions of the SCAT, further enriching the resources available in the Korean language.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. First, the on-field assessment of the translated SCAT6 did not involve field testing with concussed athletes. Although rigorous measures were taken during translation and adaptation, practical applications in the field require validation and further evaluation. Second, the validation and pre-testing phases involved a relatively small number of rugby athletes. A larger and more diverse sample size could provide a more robust assessment of the reliability and effectiveness of the tool.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study marks a significant milestone as it introduces the first valid and reliable Korean version of the SCAT6. This develop-ment holds promise for the broader Korean-speaking athletic community as it provides a dedicated concussion-specific assessment tool. The availability of such a tool in Korea is expected to enhance streamlined concussion care. The cultural adaptation and translation processes ad-hered to the established standards, ensuring that the tool retained its core purpose while being accessible to a wider audience. As the field of sports concussion management continues to evolve, this contribution is poised to have a valuable impact in the Korean context. Further research and field testing are essential to establish the validity and usability of this tool in practical sports scenarios.

Notes

The authors declare that they do not have conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: SY Ahn; Data curation: SY Ahn, J Seo, NAB Zulkifli; Formal analysis: SY Ahn; Funding acquisition: W Song; Methodology: SY Ahn; Project administration: SY Ahn; Visualization: SY Ahn, J Seo, NAB Zulkifli; Writing - original draft: SY Ahn, J Seo, NAB Zulkifli; Writing - review & editing: SY Ahn, W Song, J Seo, NAB Zulkifli.