저항성 트레이닝 강도가 건강한 성인의 동맥경직도에 미치는 영향

Effects of Resistance Training Intensity on Arterial Stiffness in Healthy Adults

Article information

Trans Abstract

PURPOSE

Resistance exercise is an effective behavioral intervention for improving skeletal muscle mass and strength, and preventing sarcopenia. However, the effects of resistance exercise on arterial stiffness remain controversial. This study aimed to organize and analyze the effects of resistance training intensity on arterial stiffness in healthy adults without overt clinical disease.

METHODS

A thorough literature search was conducted to retrieve original research articles between 2000 and 2023 using the PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases.

RESULTS

Long-term low-intensity resistance training (RT) was deemed a safe exercise intervention that can maintain or decrease arterial stiffness and increase muscle strength. Moreover, moderate-intensity RT was effective in improving muscle strength and hypertrophy but did not reduce arterial stiffness. High-intensity RT was an excellent intervention for enhancing muscle strength. However, a potential risk of increasing both central and peripheral artery stiffness in young adults was present.

CONCLUSIONS

Compared to low-intensity RT, moderate-to-high-intensity RT was more effective in improving muscle strength and hypertrophy, but may increase arterial stiffness.

서 론

저항성 운동은 근력 증가를 포함한 근육 기능 개선에 필수적인 행동 중재이며, 체지방률 감소, 기초대사량 증가, 골밀도 향상 및 노화로 인한 근감소증 방지에 효과적인 권장 신체활동 종류 중 하나이다[1,2]. 미국스포츠의학회(American College of Sports Medicine, ACSM)는 성인의 만성질환을 예방, 관리하고 건강수명을 증가시키기 위한 방법으로 규칙적인 유산소 운동과 더불어 최소 주 2회의 저항성 운동 실시를 권장한다[3]. 저항성 운동은 골격근 합성에 매우 강력한 동화 자극을 제공하며 그 종류는 근수축 형태에 따라 나뉜다. 관절의 움직임 없이 근육의 길이가 일정하게 유지되는 등척성 운동, 근육의 길이가 수축에 의해 짧아졌다가 길어지는 등장성 운동, 특수한 장비를 사용하여 일정한 속도로 근육을 수축하는 등속성 운동이 있다. 근비대, 근력, 근지구력과 같이 각각의 목적에 따라 운동 부하, 운동량, 근육의 수축 속도, 휴식시간 등에 차이가 있고 기구를 사용하거나 기구의 보조없이 맨몸으로 수행할 수 있다[4]. 운동에 대한 반응은 대상자에 따라 다를 수 있으며 젊은 성인과 노인에게 동일한 저항성 운동 프로토콜을 적용하였을 때 노인 그룹이 젊은 성인 그룹보다 근파워가 더 증가하거나, 호르몬과 신체 조성의 차이로 인해 남성이 여성에 비해 더 큰 근비대가 유도되기도 하였다[5-7].

2020년에 발행한 세계보건기구(World Health Organization, WHO) 보고서에 따르면 심혈관질환은 전 세계 주요 사망원인 중 하나이며, 심혈관질환으로 인한 사망자 수는 지속적으로 증가하는 추세이다[8]. 우리나라에서도 심혈관질환으로 인한 사망자 수는 꾸준히 증가해 왔으며 암 사망자 수 다음으로 많은 것으로 보고된다[9]. 따라서 사회적, 보건의료적 관점에서 심혈관질환의 유병률과 심혈관질환으로 인한 사망률을 낮추기 위한 지원과 노력이 강조되고 있다. 연령, 혈압, 혈중 지질 수준을 포함하여 다양한 건강 및 임상 지표들이 심혈관질환 예측 및 예방에 사용되고 있으며, 이 중 동맥경직도는 독립적으로 심혈관질환의 위험도를 타당성 있게 예측할 수 있는 비침습적 임상지표로 활용되고 있다[10]. 해부학적으로 경동맥, 대동맥아크, 복부대동맥과 같은 중심동맥은 상완동맥, 요골동맥과 같은 말초동맥보다 혈관크기 대비 평활근량이 적고 탄성단백질의 비율이 높아 노화로 인한 구조적 변화가 크고 혈관경화가 쉽게 나타난다. 기능적으로도 중심동맥은 심실수축 시 생기는 혈관벽의 충격을 흡수하여 말초 조직까지 산소와 혈액이 안정적으로 유입되는 것을 돕는다. 따라서, 중심동맥의 경직도가 상승할 경우 병리적 심실비대, 심부전, 뇌혈관질환, 말초혈관질환 등과 같은 다양한 심장 및 혈관질환의 발병원인을 제공할 수 있다[11]. 동맥경직도의 측정 및 평가를 위해 사용되는 대표적인 임상지표는 경동맥-대퇴동맥 맥파전달속도(carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity, cfPWV)이며, 추가적으로 맥파증대지수(augmentation index, AIx), 경동맥-발목 혈관지수(carotid-ankle vascular index, CAVI), 상완-발목 맥파전달속도(brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity, baPWV), 경동맥 경직도(carotid artery stiffness) 등을 측정하여 동맥의 다양한 특성을 반영한 종합적인 동맥경직도 평가가 가능하다[12-16].

규칙적인 운동은 심혈관질환 예방과 동맥경직도 개선에 도움이 된다[17]. 장기간의 규칙적인 유산소 운동은 연령, 성별, 질환여부, 운동종류와 상관없이 동맥경직도를 감소시킬 수 있는 효과적인 행동중재이다[18-22]. 다양한 연령 및 집단에서 만성질환 예방, 관리 및 삶의 질 개선을 위해 규칙적인 저항성 운동이 유산소 운동과 함께 권장되고 있다. 하지만, 동맥경직도 개선과 관련하여 저항성 운동의 실시는 여전히 논란의 여지가 있으며, 그 중심에 저항성 운동강도가 자리잡고 있음을 부인할 수 없다[23-31]. 따라서 본 종설연구는 최근까지 발표된 국내외 관련 연구들을 요약, 정리하여 저항성 운동이 동맥경직도에 미치는 영향을 운동강도별로 분류한 후, 추가적으로 연령 및 성별에 따라 동맥경직도에 미치는 영향에 차이가 있는지 분석하고자 한다.

연구 방법

본 연구를 위해 2000년 1월부터 2023년 7월까지 출간된 학술논문을 PubMed, Web of Science 및 Google Scholar 학술자료 검색 시스템을 이용하여 수집, 정리했다. 자료 조사 및 수집을 위해 ‘ low or light intensity’, ‘ moderate intensity’, ‘ high or vigorous intensity’, ‘ resistance exercise or training’, ‘ strength exercise or training’, ‘ vascular function or arterial stiffness or pulse wave velocity or augmentation index or arterial compliance or β-stiffness’, ‘ young’, ‘ middle aged’, ‘ older or elderly’ 등의 키워드를 조합하여 검색 시스템에 적용했다. 자료분석의 정확도를 높이기 위해 무작위 대조실험(randomized controlled trial, RCT)에 기반하여 건강한 성인을 대상으로 3주 이상의 역동적(등장성) 저항성 트레이닝을 실시한 운동중재 연구만 본 종설연구에 포함시켰으며, ACSM 운동처방 지침을 참고하여 저강도 저항성 운동강도는 최대 1회 반복중량(1 repetition maximum, 1RM)의 50% 이하로, 중강도 저항성 운동강도는 1RM의 50-70%로, 고강도 저항성 운동강도는 1RM의 75% 이상으로 설정하여 자료조사를 실시했다[32,33]. 심혈관질환을 포함한 임상질환자를 대상으로 진행한 연구, 남성과 여성의 데이터가 혼합 제시되어 성별에 따라 구분된 데이터를 확보할 수 없는 연구, 운동강도가 명확히 제시되지 않은 연구, 등척성 또는 등속성 수축에 기반한 저항성 운동을 실시한 연구, 국문과 영문 이외의 언어로 작성된 문헌은 본 연구에서 제외했다.

연구 결과

1. 동맥경직도

심혈관질환의 독립적 예측인자로서 동맥경직도는 동맥벽의 구조적, 기능적인 변화로 인해 본래의 탄성을 잃고 딱딱해진 상태를 의미한다. 동맥벽은 혈관내피세포와 혈관 민무늬근을 포함한 다양한 해부학적 구조물에 의해 이루어져 있다. 이 중 엘라스틴과 콜라겐 섬유가 동맥벽의 구조적 특성을 좌우하는 중요한 물질이며, 일반적으로 동맥벽에는 탄성단백질인 엘라스틴 비율이 비탄성섬유인 콜라겐에 비해 높은 것으로 알려진다[34,35]. 혈관벽에서 엘라스틴의 기능적 역할은 심주기에 맞춰 동맥을 이완시키는 것이며, 콜라겐 섬유는 혈관의 해부학적 견고함을 유지, 강화하는 특징이 있다. 인체의 동맥 네트워크에서 구조적으로 엘라스틴의 비율이 높은 혈관조직은 심장에 가장 가까이 위치한 대동맥이다. 이런 해부학적 위치 및 특성에 기인하여 대동맥은 심주기동안 나타나는 압력변화에 대응하여 심장으로부터 형성된 급격한 혈압의 증가를 완화시키는 완충작용을 통해 체내 말단 조직까지 안정적으로 산소와 혈액을 공급할 수 있는 환경을 마련한다[36]. 안타깝게도 다른 말초동맥에 비해 중심동맥인 대동맥에서 퇴행성 변화를 동반하는 노화에 의해 쉽게 동맥경직도 증가가 나타난다[37].

동맥경직도가 증가하는 원인은 크게 구조적, 기능적인 변화로 구분할 수 있다. 일반적으로 구조적인 퇴행성 변화는 장기간에 걸쳐 이루어지며, 엘라스틴 단백질의 파편화, 혈관벽 내 콜라겐 섬유의 증가, 엘라스틴 단백질과 콜라겐 섬유의 가교 결합(cross-linking)이 대표적인 해부학적 변화 양상으로 나타난다[34]. 이런 동맥벽의 구조적인 퇴행성 변화는 동맥벽의 탄력을 감소시켜 혈관을 더욱 뻣뻣하게 만들며, 혈관벽의 내중막두께 증가로 나타난다[38]. 혈관내피세포 기능 부전은 동맥벽의 기능적인 퇴행성 변화와 밀접한 관련이 있다. 건강한 상태의 혈관내피세포는 산화질소를 생성, 방출하여 자극에 대한 동맥벽의 확장성 반응을 일으킨다. 그러나, 혈관내피세포 기능 부전이 나타나면 혈관 내 산화스트레스 수준 증가, 염증 전구물질 증가 및 산화질소 합성효소(eNOS)의 하향 발현 등이 나타나 산화질소 생성을 감소시키거나 산화질소의 혈관 내 생이용성을 감소시킬 수 있다. 이는 직접적으로 동맥벽의 확장성 반응을 약화시켜 동맥경직도 증가의 원인을 제공할 수 있다[39]. 또한 체내 교감신경계 활성화는 심박수, 심박출량, 혈관저항 증가를 초래해 고혈압 및 좌심실비대를 초래할 뿐만 아니라 골격근을 포함한 말초혈관조직의 교감신경계 활성화로 연결되어 연령 및 성별과 상관없이 동맥경직도를 증가시키는 원인을 제공한다[40,41]. 추가적으로 노화는 동맥벽의 퇴행성 구조 변화에 영향을 미쳐 병적 대동맥 확장 및 동맥경화로 진행될 수 있으며, 유전, 흡연 및 신체활동량도 동맥경직도 증가와 밀접한 관련이 있다[42-45].

인간을 대상으로 동맥경직도를 평가하는 방법으로 자기 공명(Mag-netic resonance, MR) 및 초음파 시스템을 이용한 맥파속도의 측정, 표준 압력 커프를 사용하여 수집한 상완에서의 동맥 압력 파형의 특징 분석 등 다양하나, cfPWV가 중심 동맥경직도를 평가하는 표준으로 임상에서 광범위하게 활용되고 있다[16]. 맥파전달속도는 심장의 수축기 동안 생성된 압력파가 동맥벽을 따라 이동하는 속도로 정의되는데, 속도가 빠를수록 동맥의 탄력도와 순응도가 낮고 경직도가 높다는 것을 의미한다[46]. 맥파전달속도 측정 시 압력(장력) 센서, 도플러 플로우미터 및 에코트래킹 등의 연구기법과 장비를 활용하여 동맥 네트워크의 두 지점에서 맥압파형을 획득한 후, 두 지점의 맥압파형 간 foot-to-foot 방법을 적용하여 맥압파형 간 시간차를 구한 후 두 지점 간의 거리를 맥압파형 간 시간차로 나눠 맥파전달속도를 산출한다[16]. 임상적으로 중심동맥의 맥파전달속도가 1 m/s 증가하면, 심혈관질환의 발병률이 14%, 심혈관질환으로 인한 사망률이 15% 증가한다[10].

AIx는 중심동맥의 압력파형을 분석하여 혈관분지에서 발생한 반사맥파의 크기와 속도를 산출, 반영한 비침습적인 동맥경직도 평가 지표로 대동맥 맥압 대비 반사맥파에 의해 증폭된 압력의 비율로 계산된다[15,47]. 임상적으로 AIx는 대동맥의 탄력성이 감소하면서 심박출 시 생성되는 혈압의 전진맥파와 말초의 분지에서 반사되어 돌아오는 반사맥파의 이동속도가 모두 증가하여 심장의 부담도가 높아지는 정도를 반영한다[48]. 따라서 AIx는 심혈관질환 위험도와 정적 상관관계를 가지고 있으며, 남성의 경우, AIx가 12.3% 증가할 때 사망률이 1.4배 증가한다고 알려져 있다[49,50].

동맥경직도 증가에 의한 심혈관질환 발병 기전은 아직까지 명확하지 않으며, 관련 연구가 지속적으로 이루어지고 있다. 다만, 동맥경직도가 증가하면 동일한 심박출량을 유지하기 위해 심근은 강한 수축을 통해 더 높은 수축기 압력을 생성해야 하고 이는 심근의 산소요구량 증가 및 좌심실 비대를 초래할 수 있다[51]. 좌심실 비대는 심부전, 관상동맥질환, 부정맥을 포함한 심혈관질환 및 모든 원인으로 인한 사망률 증가와 밀접한 관련이 있는 것으로 보고된다[52]. 추가적으로 동맥경직도의 증가는 말초 조직에 요구되는 혈액과 산소 공급을 제한하여 표적장기손상을 유발할 수 있으며, 표적장기손상은 심혈관질환 발병 위험을 증가시킬 수 있다[53,54].

2. 저-중강도 저항성 운동과 동맥경직도

미국스포츠의학회에서는 근력증가와 근비대를 위한 저항성 운동강도로 1RM의 60-85% 수준을 권장하며, 초보자의 경우 정확한 운동수행과 근골격계 부상을 예방하기 위해 저-중강도에 해당하는 1RM의 50-60% 수준을 권장한다[4]. 일반적으로 근비대 및 근력향상을 위한 저항성 트레이닝 운동강도로 중강도 이상이 권장되지만 저강도 저항성 운동만으로도 근력 및 근비대 개선에 도움을 줄 수 있다. 젊은 남성을 대상으로 10주간의 저항성 트레이닝이 근단백질 합성 신호전달 및 근비대 개선에 미치는 효과를 분석한 선행연구에서 저강도 저항성 트레이닝과 고강도 저항성 트레이닝 간 운동효과에 유의한 차이가 나타나지 않았으며[55], 중년여성을 대상으로 12주간의 저강도 저항성 트레이닝을 실시한 결과 트레이닝 전과 비교해 유의한 근단면적 증가와 근력향상이 나타났다[56]. 이는 제한적이지만 연령 및 성별에 관계없이 저강도 저항성 운동만으로도 근력 및 근비대의 개선을 유도할 수 있다는 것을 시사한다.

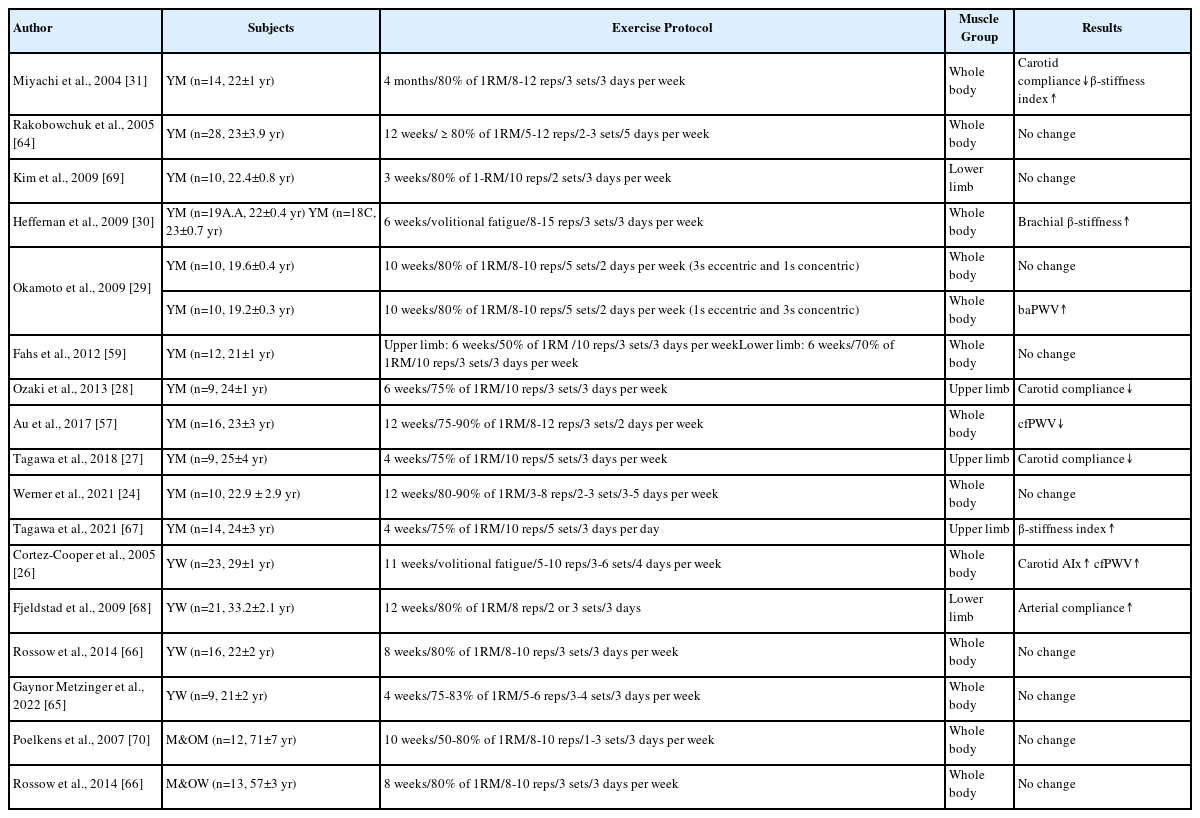

저항성 운동은 주로 근골격계의 구조적 견고함과 기능수행 향상을 목적으로 수행되지만, 저-중강도 저항성 운동은 근육의 해부생리적 적응과 더불어 동맥경직도 개선에도 도움을 줄 수 있다. 동맥경직도와 관련하여 저강도 저항성 트레이닝은 운동 중 혈압상승의 폭을 제한하기 때문에 고강도 저항성 트레이닝에 비해 동맥경직도에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 가능성이 낮다. 저-중강도 저항성 트레이닝이 건강한 성인의 동맥경직도에 미치는 효과는 Table 1에 제시되어 있다. 젊은 남성을 대상으로 실시한 12주간의 저강도 저항성 트레이닝은 동맥경직도의 대표적인 임상지표인 cfPWV를 유의하게 감소시켰고[57], 8주간의 저강도 저항성 트레이닝은 baPWV를 유의하게 감소시키는 것으로 나타났다[58]. 그러나, 기간이 단축된 6주간의 저강도 저항성 트레이닝은 젊은 남성의 동맥경직도를 감소시키지 못했다[59]. 노화에 의해 혈관기능의 감소가 나타나는 중년 여성의 경우, 젊은 성인과 달리 12주간의 저강도 저항성 트레이닝으로 안정 시 혈압과 동맥경직도 지표인 cfPWV, baPWV, 대퇴동맥-발목 맥파전달속도(femoral-ankle pulse wave velocity, faPWV), AIx, 심박수 75회로 보정한 맥파증대지수(augmentation index adjusted at 75 beats per minute of heart rate, AIx@75)를 감소시키지 못했다[60]. 임상 질환이 없는 건강한 성인을 대상으로 중강도 저항성 운동이 동맥경직도에 미치는 영향을 분석한 선행연구는 제한적이다. 젊은 남성을 대상으로 실시한 12주간의 중강도 저항성 트레이닝은 동맥경직도 관련 지표를 개선시키지 못했으며[24], 중년 여성을 대상으로 실시한 12주와 18주간의 중강도 저항성 트레이닝 역시 동맥경직도를 감소시키지 못했다[23,25]. 고혈압을 가진 중년 성인을 대상으로 실시한 4주간의 중강도 저항성 트레이닝은 남성의 경우 동맥경직도를 유의하게 증가시켰으나, 여성의 동맥경직도에는 아무런 영향을 미치지 않았다[62].

건강한 젊은 성인을 대상으로 근력 증가와 함께 동맥경직도 개선 효과를 기대하기 위해서는 최소 8주 이상의 저강도 전신 저항성 트레이닝이 요구되며, 중년 성인 및 노인의 경우 동맥경직도 개선을 위해 더 장기간의 저강도 저항성 트레이닝이 필요한 것으로 추정된다. 중강도 저항성 트레이닝은 건강한 성인의 동맥경직도 개선에 도움을 주지 못하며, 고혈압을 가진 중년 남성의 경우 단기간의 중강도 저항성 트레이닝으로도 동맥경직도가 증가될 가능성이 있어 운동프로그램 제공 시 주의할 필요가 있다.

3. 고강도 저항성 운동과 동맥경직도

고강도 저항성 운동은 근골격계가 고중량 부하를 견디는 움직임으로 이루어진다. 고중량 부하에 대항하여 근수축이 이루어질 경우 체간의 안정성 확보를 위해 자연스럽게 발살바 호흡(Valsalva manuever)이 동반될 수 있다[63]. 발살바 호흡에 의한 복압의 증가는 해부학적 위치상 사지에 있는 말초 혈관보다 복부대동맥, 대동맥아크, 경동맥과 같은 중심 동맥의 경직도에 영향을 미치기가 쉽다. 고강도 저항성 트레이닝이 동맥경직도에 미치는 영향은 연령, 성별, 운동부위, 동맥경직도 지표에 따라 다소 차이가 있다.

Table 2는 고강도 저항성 트레이닝이 건강한 성인의 동맥경직도에 미치는 영향을 조사한 선행 연구결과를 요약, 정리한 내용을 보여준다. 건강한 젊은 남성을 대상으로 실시한 6주 이상의 고강도 전신 저항성 운동은 동맥경직도를 개선시키지 못하고[29,59,64] 오히려 동맥경직도 지표인 경동맥 순응도(carotid artery compliance)를 감소시키고, 경동맥과 상완동맥의 베타-경직도 지표(carotid and brachial artery β-stiffness index)와 baPWV를 증가시키는 것으로 나타났다[29-31]. 건강한 젊은 여성을 대상으로 실시한 고강도 전신 저항성 트레이닝도 남성과 유사하게 동맥경직도를 개선시키지 못하거나[65,66], cfPWV와 AIx를 증가시키는 것으로 나타났다[26]. 하지만, 6주간의 고강도 전신 저항성 트레이닝으로 동맥경직도 증가가 나타나는 남성에 비해 여성은 11주 이상의 고강도 전신 저항성 트레이닝을 실시할 때 동맥경직도 증가가 나타났다[26]. 부위별 저항성 트레이닝이 건강한 젊은 성인의 동맥경직도에 미치는 영향을 살펴보면, 단지 4주간의 고강도 상체 저항성 운동만으로도 경동맥 순응도를 감소시키고, 경동맥 베타-경직도 지표를 증가시키는 것으로 나타났다[27,28,67]. 그러나, 고강도 하체 저항성 운동은 동맥경직도에 부정적이지 않고 오히려 동맥순응도를 개선시키는 것으로 나타났다[68,69]. 흥미롭게도, 동일한 고강도 저항성 트레이닝을 실시하더라도 근수축 형태별 지속시간에 따라 동맥경직도 반응 및 적응에 차이가 나타날 수 있다. Okamoto 등의 연구에서 건강한 젊은 남성을 대상으로 10주간의 고강도 전신 저항성 트레이닝을 실시했을 때, 신장성 수축시간을 길게 처치한 집단보다 단축성 수축시간을 길게 처치한 집단에서 baPWV가 유의하게 높은 것으로 나타났다[29].

임상질환이 없는 상대적으로 건강한 중-노년 성인을 대상으로 고강도 저항성 운동이 동맥경직도에 미치는 영향을 분석한 연구는 매우 제한적이며, 남성과 여성 모두 10주 이하의 고강도 전신 저항성 트레이닝이 동맥경직도 변화에 영향을 미치지 못했다[66,70].

4. 저항성 운동에 의한 동맥경직도 변화의 잠재적 기전

저항성 운동 시 발살바 호흡에 의한 혈압의 상승은 동맥경직도 증가의 원인을 제공할 수 있다. 발살바 호흡이 동반되는 1RM의 85% 이상 강도로 레그프레스 운동을 실시했을 때 평균 수축기 혈압이 311 mmHg, 평균 이완기 혈압이 284 mmHg까지 증가한다는 연구결과와 발살바 호흡을 동반한 저항성 운동이 발살바 호흡을 동반하지 않은 저항성 운동에 비해 중심 동맥경직도를 유의하게 증가시켰다는 선행 연구결과는 장기간의 강도 높은 저항성 운동은 반복적인 혈압의 급격한 상승을 유발하여 동맥벽의 탄력성 구조물인 엘라스틴을 손상시키고, 단단한 섬유질로 구성된 콜라겐 생성을 촉진하여 결국 동맥벽의 구조를 부정적으로 변화시킬 수 있음을 암시한다[28,29,31,71,72]. 그러나, 저강도 저항성 운동은 상대적으로 운동 중 혈압의 상승폭이 작고, 혈압의 급격한 상승을 동반하지 않기 때문에 동맥벽의 해부학적 변화로 인한 동맥경직도 증가를 일으킬 가능성이 낮고 오히려 규칙적인 유산소 운동 시 나타나는 혈류역학적 반응 및 적응으로 인한 동맥경직도 개선 효과와 유사한 메커니즘으로 동맥경직도를 감소시킬 수 있다[73]. 혈압의 조절은 교감신경계의 활성화 및 혈장 카테콜라민 수준과 관련이 있다. 저항성 운동 시 교감신경계 말단과 부신 수질에서 분비되는 노에피네프린과 에피네프린은 동맥벽에 위치한 아드레날린 수용체와 결합하여 혈관 평활근 장력을 증가시킬 수 있다[74]. 일반적으로 고강도 저항성 운동은 혈장 노에피네프린 농도를 증가시키지만 저강도 저항성 운동은 혈장 카테콜라민 농도에 영향을 미치지 않는다[75]. 이는 고강도 저항성 운동으로 인한 교감신경계 활성화 및 혈장 카테콜라민 수준 증가가 저-중강도와 달리 고강도 저항성 트레이닝 후 동맥경직도를 증가시키는 부분적인 원인을 제공한다. 단지 일회성 저항성 운동만으로도 혈관내피세포에서 생성, 분비되는 혈관수축 물질인 혈장 엔도텔린 1(endothelin-1, ET-1) 수준이 증가될 수 있으며, 이는 저항성 운동에 의한 동맥경직도 증가의 생리적 기전으로 작용할 수 있다[76]. 그러나, 저-중강도 저항성 운동보다 고강도 저항성 운동이 혈장 ET-1 수준을 유의하게 증가시킨다는 과학적 증거는 아직까지 부족한 실정이다. 마지막으로 저항성 운동 시 강한 힘을 생성하기 위해 근수축에 동원되는 근육량이 많아지면 말초혈관의 저항을 급격히 증가시킬 수 있다. 말초 혈관저항의 급격한 증가는 운동 중 순환계에 역행(retrograde) 혈류를 증가시켜 순행(anterograde) 혈류의 흐름을 방해할 수 있다. 이는 동맥벽 확장에 중요한 생리적 자극인 전단응력(shear stress)을 감소시켜 혈관내피세포에서 산화질소 분비를 감소시키고 결과적으로 제한된 혈관확장에 의한 동맥경직도 증가를 초래할 수 있다[62].

결 론

장기간의 저강도 저항성 트레이닝은 근력 증가와 함께 동맥경직도를 유지, 개선시킬 수 있는 가장 안전한 저항성 운동이다. 중강도 저항성 트레이닝은 근비대 및 근력 증가에 효과적이지만 동맥경직도를 개선시키지 못한다. 고강도 저항성 트레이닝은 근력 향상에 탁월한 효과를 보이지만, 특히 젊은 성인의 경우 중심과 말초 동맥경직도를 모두 증가시킬 수 있는 위험성이 존재한다. 하체 위주로 구성된 고강도 저항성 운동은 동맥경직도를 유지, 개선시킬 수 있으나 상체 위주로 구성된 고강도 저항성 운동은 동맥경직도에 부정적인 영향을 미칠 수 있다. 고강도 저항성 운동이 동맥경직도를 증가시키는 생리적 기전은 아직까지 명확하지 않지만, 운동 중 급격한 혈압 상승, 동맥 탄력성 감소를 동반한 해부학적 변화, 교감신경계의 활성화, 역행혈류 증가에 의한 혈관내피세포 기능 감소 등이 관련되는 것으로 추정된다. 중-고강도 저항성 운동과 유산소 운동이 결합된 복합운동은 효과적으로 근력과 근육량을 증가시키면서 심혈관질환 위험을 감소시킬 수 있는 대안적 행동중재로 활용될 수 있다.

Notes

이 논문 작성에 있어서 어떠한 조직으로부터 재정을 포함한 일체의 지원을 받지 않았으며, 논문에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 어떠한 관계도 없음을 밝힌다.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: JS Son, MH Hwang; Data curation: JS Son, R Lee; Formal analysis: JS Son, MH Hwang; Funding acquisition: MH Hwang; Methodology: JS Son, R Lee, MH Hwang; Project administration: MH Hwang; Visualization: JS Son; Writing - original draft: JS Son, MH Hwang; Writing - review & editing: R Lee, MH Hwang.