Effects of Aquatic Training on Waist Circumference and Body Composition among Children: A Meta-analysis

Article information

Trans Abstract

PURPOSE

Aquatic training assists in reducing the risk of exercise on joints among children. This systematic review evaluated the effectiveness of aquatic training for children from the perspective of body composition.

METHODS

A meta-analysis was performed to determine the potential impact of aquatic training in children. Four databases, namely Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, and EBSCO, were used for the systematic search from September 2010 to November 2021. The mean differences in the data were analyzed using Stata 15.1 software with a 95% confidence interval. Outcome measures included weight, body mass index (BMI), fat percentage (Fat%), and waist circumference.

RESULTS

Eleven studies, comprising eight randomized controlled trials (RCT) and three non-RCT studies, evaluating the effect of aquatic training on children were analyzed and reported. Aquatic training significantly improved the BMI (p<.01) and Fat% (p<.01) in children (ES (95% CI)=−0.23 (−0.38, −0.08) and ES (95% CI)=−0.27 (−0.45, −0.08). However, aquatic training had no significant effect on weight (p=.41), ES (95% CI)=−0.07 (−0.25, 0.10), and waist circumference (p=.11) in children, ES (95% CI)=−0.33 (−0.74, 0.08).

CONCLUSIONS

Aquatic training can improve children's BMI and body fat% but nottheir weight, waist circumference, and muscle mass. Aquatic training may be a potential exercise program for improving body composition in children.

INTRODUCTION

Overweight and obesity are common outcomes of insufficient amount of physical activity and improper diet in children and adolescents, whereas body fat content is reduced in prepubertal children by engaging in intensified physical activity [1,2]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) states that children should be encouraged to participate in various kinds of physical activity to improve cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness and reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression [3]. Following the WHO recommendations, American, African and European governmental organisations have developed guidelines on the recommended daily amount of physical activity for children according to regional context [4,5]. In most countries, it is recommended that children participate in moderate or vigorous-intensity exercise for a minimum of 60 minutes per day.

Regular physical activity, if performed at a sufficient intensity and with adequate frequency, has a positive effect on musculoskeletal health and adiposity [6]. For obese individuals, aquatic activities are considered as exercise alternatives based on the physical properties of water, particularly the fluctuation of water current [7]. Aquatic training refers to the routine exercise with or without equipment in the water, which may be more interesting and novel for children, and may enhance motivation and interest [8]. These activities assist in reducing the effects on the joints that play a vital role in supporting body weight. Furthermore, it is emphasised that deep-running or walking can be executed with or without using float equipment as part of aquatic activities. Given the viscosity of water, the drag generated in aquatic activities is relatively higher. Besides the reduction of joint stress, higher energy expenditure is provided when walking in water to overcome the associated resistance [9,10].

It remains unclear if aquatic training can improve children's waist circumference and body composition. For instance, children that engaged in aquatic training three times per week experienced an improvement in body mass index (BMI) and body fat rate (Fat%) [11,12]; however, other researchers reported contradicting outcomes [13,14]. Therefore, this systematic review evaluates the effectiveness of children's aquatic training from the perspective of body composition, especially BMI and Fat%. The findings will provide a theoretical basis for the application of aquatic training in children's training.

METHODS

1. Registration and Protocol

The review protocol was registered with the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols on October 19, 2021 (PROSPERO registration number: CRD42021279486).

2. Study Selection and Data Sources

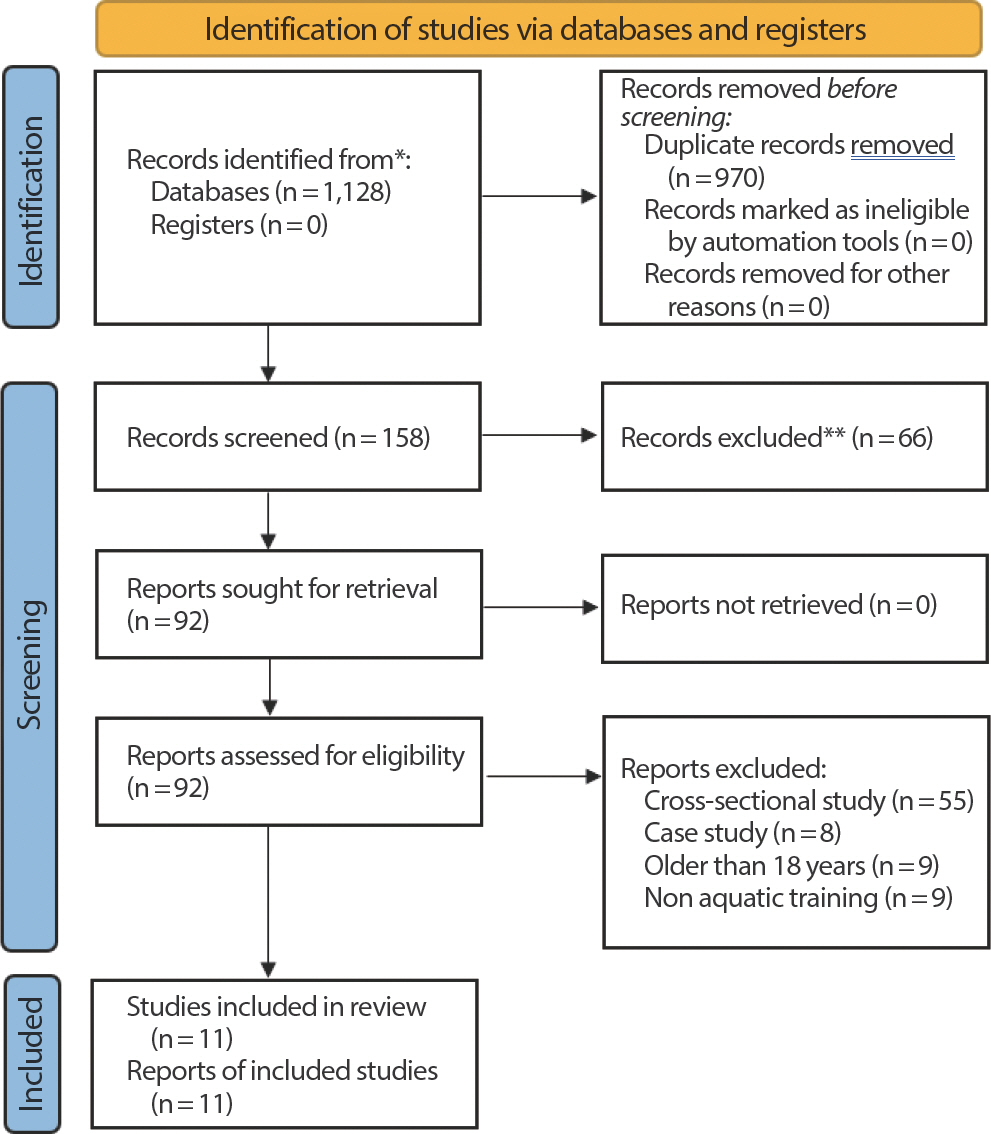

Four databases, namely, Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, and EBSCO were used for the systematic search from September 2010 to November 2021. The search terms used were “ Child”, “ Training”, “ Exercise”, “ Swim”, “ Aquatic”, and “ Water”. Fig. 1 and Appendix present the detailed search strategy.

The titles and abstracts retrieved from the databases were screened independently by two investigators. Each study was summarised by extracting specific information, including the year of publication, first author, gender and age of the studied population, training programme, intervention duration, main indicators and sampling method of body fat rate. In cases where further information was required, corresponding authors of the articles were contacted via electronic mails. In addition, a third investigator was requested whenever the two investigators responsible for extracting information from the articles experience a dispute. Hence, the issue was resolved based on the opinion from the third investigator and further discussion with other investigators (see Table 1).

3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Several criteria were applied in deciding the articles to be included or excluded from the systematic review. Interventional studies that involved aquatic training in children were included. Nevertheless, a minimum of four weeks was required for the intervention to be included. Furthermore, the studies must be written in English and investigated at least either one or a combination of the following variables: weight, BMI, Fat% and waist circumference. All controlled trials, whether randomised (RCT) or non-RCT, were included in this systematic review. Articles were not considered if they were abstracts, conference presentations or proceedings.

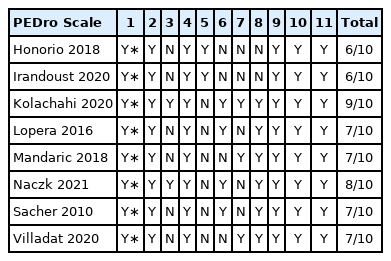

4. Quality Assessment

All the RCTs were checked for quality using the PEDro scale [15]. A total of 11 questions are present in the PEDro scale. An RCT study is considered to be of high-quality RCT if a score of six or above is obtained [16]. For non-RCT studies, the "Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) was applied to assess the quality with No Control Group" (NIH) scale [17]. Given that NIH consisted of 12 questions, the quality of each study was categorised as “ good”, “ fair” or “ poor”.

5. Risk of Bias Assessment

The studies were excluded one after the other to perform the sensitivity analysis. This procedure was used to determine the stability of the meta-analysis findings. A funnel plot was applied to analyse the study publication bias.

6. Data Analysis

All data analyses were performed using Version 21 of STATA 15.1 for Windows (College Station, TX, United States of America). Mean±stan-dard error were computed using descriptive statistics and applied in summarising the waist circumference and body composition. Treatment effects were measured based on the mean difference pre-and post-intervention and the estimates were presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The method outlined in the Cochrane Handbook (https://training. cochrane.org/ handbook) was used for the calculation.

Statistical heterogeneity between the studies was assessed using the Q test and I2 statistics. These statistical tests, especially the Q test, determined the type of model to be applied. If a significant heterogeneity (p <.05 or I2 >50%) is detected, a random-effect model was used. In contrast, a fixed-effect model was built if considerable heterogeneity is lacking. This systematic review was developed by following the Meta-Analysis Report Quality statement guidelines [18].

RESULTS

1. Eligibility of Studies

A Cohen kappa coefficient of 0.923 was obtained between the search conducted by the two investigators. A total of 11 studies evaluating the effect of aquatic training on children were analysed and reported, comprising eight RCT and three non-RCT studies (Table 1). The pre-determined inclusion criteria were met by all the studies. Due to the small sample size of the RCT studies, this single-arm meta-analysis approach was employed to process the data. Also, it was verified that all the included studies obtained ethical approval from their respective institutions before performing the study protocol. All the studies included BMI as a parameter, whereas nine included weight, eight considered Fat% and waist circumference was reported in three studies. A total of 332 children were included with an average age of 11.8 years. The duration of training applied as an intervention in the various studies ranged from six weeks to 36 weeks.

2. Quality Assessment

All the RCT studies [11-14,19-22] were considered to have high quality, as the total scores obtained from the PEDro scale for each study was greater than 5. For the non-RCT studies [23–25], the general quality rating was classified as "Good" according to the NIH scale (Table 2).

3. Quantitative Synthesis

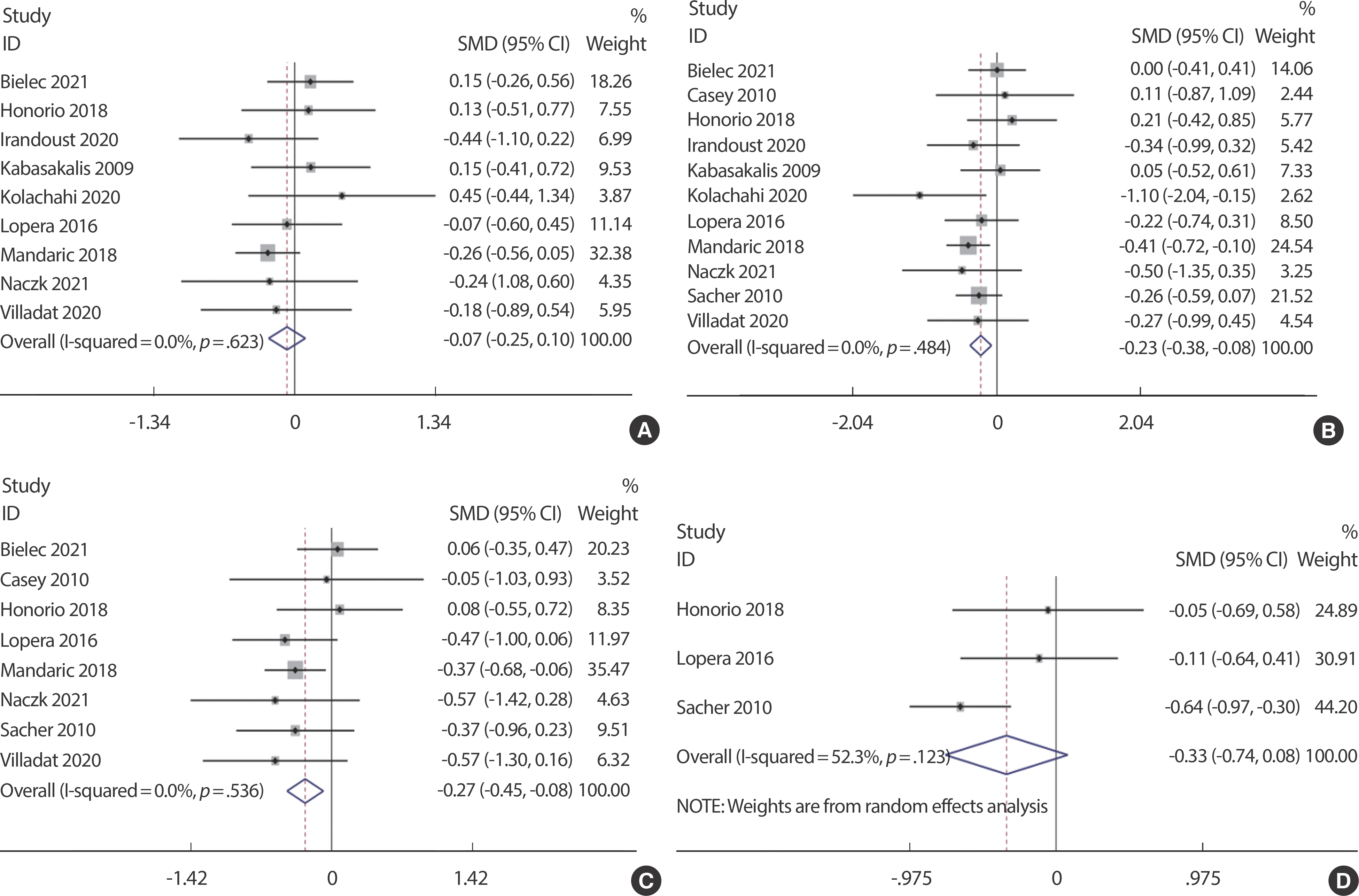

The effects of aquatic training on children’ s weight in children (n= 164) was evaluated in nine studies. Based on the findings of the one-arm meta-analysis, aquatic training had no significant effect in improving children’ s weight (p =.41, z=0.82), ES (95% CI)=−0.07 (−0.25, 0.10) (Fig. 2A). Moreover, the studies lacked heterogeneity in accordance with the findings from the heterogeneity test (p =.62, I2 =0%).

The forest plot of the effect size for studies assessing the effect of aquatic training on the weight (A), BMI (B), Fat% (C) and waist circumference (D) among children.

The impacts of aquatic training on BMI and Fat% in children was evaluated in 11 and 8 studies, respectively (n=164). Furthermore, one-arm meta-analysis revealed that aquatic training significantly improved the BMI (p <.01, z=2.94) and Fat% (p <.01, z=2.84) in children, ES (95% CI)=−0.23 (−0.38, −0.08) (Fig. 2B) and ES (95% CI)=−0.27 (−0.45, −0.08) (Fig. 2C). The heterogeneity test results showed no heterogeneity between the studies (p =.48, I2 =0% and p =.54, I2 =0%).

Three articles evaluated the relationship between aquatic training and children’ s waist circumference (n=164). One-arm meta-analysis showed that aquatic training had no significant effect on waist circumference (p =.11, z=1.59) in children, ES (95% CI)=−0.33 (−0.74, 0.08) (Fig. 2D). Likewise, no heterogeneity was detected between the studies as per the heterogeneity test results (p =.12, I2 =52.3%).

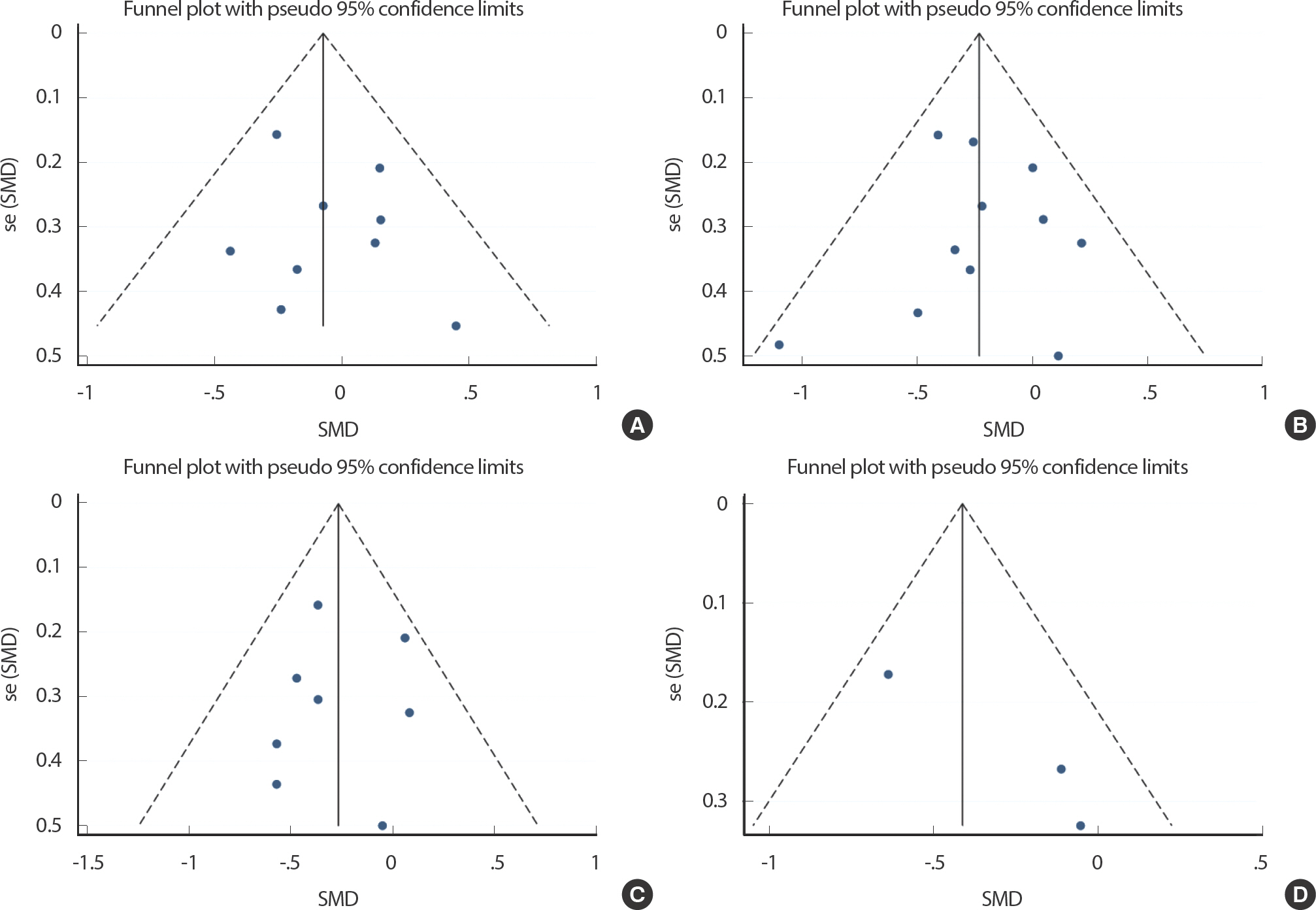

4. Sensitivity Analysis

A step-wise sensitivity analysis was performed by changing the analysis model, selecting the effect size, and removal of individual articles. Despite some of the studies lacked any sign of heterogeneity, the sensitivity analysis was still performed to ensure data accuracy and stability. The findings demonstrated that no article significantly interfered with the meta-analysis results, thereby indicating the outstanding stability of the present study. Fig. 3 depicts the sensitivity analysis for waist circumference and body composition, respectively.

5. Analysis of Publication Bias

A funnel plot was employed to analyse the potential publication bias in this systematic review. As the sample size was relatively small for aquatic training on children, only eight studies were included in the analysis. Given that the total sample size used was close to the minimum requirement for funnel plot analysis, the analysis is still considered capa-ble of reflecting a certain degree of publication bias despite the minor risks. The feasibility of using funnel analysis for small sample size studies has been demonstrated in a previous study (Fig. 4) [26].

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this meta-analysis was to determine the effects of aquatic training on children's waist circumference and body composition. A total of 11 studies were included in this review with three evaluating the effects of aquatic training on waist circumference, whereas nine articles investigated the effects on body weight. Furthermore, 11 and 8 articles evaluated the effects on BMI and body fat rate, respectively. A meta-analysis of the current literature shows that aquatic training significantly improved children's BMI and body fat rate. It also suggests that aquatic training may be a safe and effective exercise programme to improve children's body composition.

Aquatic training had no significant effect on the children’ s weight in this study. This is consistent with the outcomes from previous research. BMI decreased significantly after aquatic training, which may be related to the simultaneous occurrence of height gain and weight loss in children after a long-term intervention. Nevertheless, the present results revealed that no significant changes in body weight were detected before and after the intervention. This might be related to the increase in muscle mass and bone mass rather than fat mass. The results showed that the body fat rate was significantly reduced. Higher BMI and body fat rate are closely related to health problems in children's growth and development [27].

Oxidative stress may be induced in obese children, which might be associated with an irregular production of adipokines, thereby contributing to the onset of metabolic syndrome [28]. Aquatic exercise elicits an easier and safer approach for children to become more active and minimise body fat in line with hydrodynamic principles (resistance, buoyancy, viscosity, relative density, turbulence, hydrostatic pressure, and flow) [29]. Disabled children were also reported to experience positive effects in terms of body composition and physical fitness following their engagement in exercise programs [30,31]. A study observed that BMI of children with autistic spectrum disorder was significantly reduced after being exposed to aquatic exercise training and combined programme [12]. These outcomes corroborate some of the findings by Mandaric and Sibinovic [11], where BMI was significantly reduced in subjects who engaged in weekly aquatic training thrice in 8 weeks. Obese adults (n=57) who trained on an aquatic and conventional treadmill for 12 weeks also experienced similar improvements in terms of body weight, VO2 max, body mass index, fat mass (percentage and absolute values) and body mass index [32]. In addition, in the cold environment (9°C) of the swimming pool, it may further increase energy consumption during exercise and promote fat metabolism through the loss of body heat [33]. However, other researchers have contradicting views. Honorio et al. [19]. pointed out that 6-week swimming combined with aquatic training did not affect BMI and Fat%. The whole-body fat might be reflected by BMI; nevertheless, it does not directly measure the body composition. This makes it not applicable to children since their lean mass is generally higher than older adults [34]. Therefore, it is important to focus on the change in body fat rate.

Over waist circumference has been associated with an increased risk of death by 20% among adults [35], and contributes significantly to health challenges [36,37]. Waist circumference is a marker of visceral adiposity and is considered a vital risk factor for metabolic syndrome. Moreover, the risk of cardiovascular disorders is associated with exces-sive abdominal fat in children. Hence, researchers are encouraged to better evaluate the effectiveness of obesity treatment [38,39]. Despite the reduction in participants’ body fat upon using waist circumference response is more objective and valuable than BMI, only three articles considered waist circumference in this systematic review. The reason is that the goal of exercise intervention is physical activity, which aims to reduce body fat and increase lean weight. Since BMI is unable to differentiate between lean mass and fat, the increase of lean may mask the decrease of fat. This event does not affect waist circumference because it does not depend on lean mass [38]. Compared to BMI, this advantage exceeds the known disadvantages of greater waist measurement error and greater variation over time. Although it is more accurate to use body fat rate to reflect the effect of fat reduction, waist circumference deserves more attention as a more convenient auxiliary index. In Sacher's study [20] the waist circumference of children in the intervention group decreased by 4.1 cm, which is in line with the outcomes reported in two other randomised studies [40,41] and two studies on the efficacy of obesity drugs [42,43]. Conversely, the present results revealed that aquatic training does not improve waist circumference, which might be due to the low number of included studies. These findings are consistent with Honorio's study [19], which pointed out that there is no significant difference in the change of waist circumference of healthy children after six weeks of swimming and water walking training. Conclusively, aquatic training may be a potential and safe fat reduction programme for children.

There are also many limitations to this study. Firstly, a large number of people were included in the study, but there was no subgroup analysis due to low heterogeneity. Secondly, there is data paucity on waist circumference and muscle mass and the reliability of the results is poor. Updated literature in future studies can be further included for analysis. Finally, whether the effect of aquatic training is better than that of non-aquatic training still needs to be included in more RCT studies. The underlying mechanism of fat reduction by aquatic training needs to be further explored in future studies. Because the training mode, intensity and duration included in the study are different, it is difficult to classify and analyze subgroups. However, the small heterogeneity (0%) of meta-analysis, all training programs are considered as aquatic training, which eliminates the interference of training programs on the results.

CONCLUSION

Aquatic training can improve children's BMI and body fat rate rather than weight, waist circumference and muscle mass. Aquatic training may be a potential exercise programme to improve body composition among children.

Notes

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization: A Khairani; Data curation: J Zhou; Formal analysis: J Zhou; Funding acquisition: A Khairani; Methodology: J Zhou, A Khairani; Project administration: Visualization: Writing - original draft: Writing - review & editing: A Khairani.